Shravasti Dhammika, in his notorious book “The Broken Buddha”, attempted to make some negative points against Theravada.

The Broken Buddha by S.Dhammika:

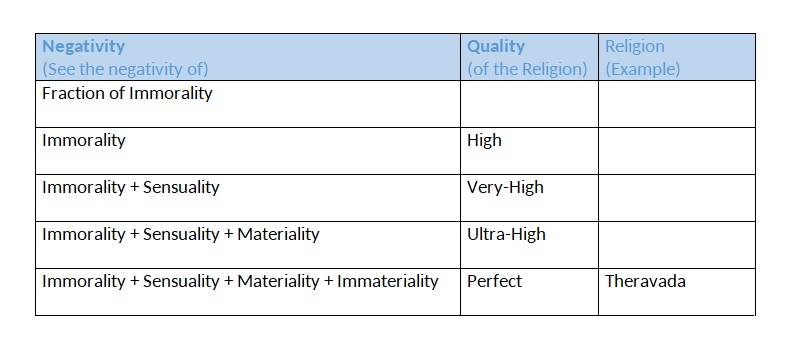

“Theravada certainly has a marked negative outlook, negativity being the tendency to consider only the bad, the ugly or the deficient side of things…When we look at Theravadin discourse on virtue we see this same tendency. The first chapter of the Visuddhimagga, that great compendium of Theravada, is entitled ‘A Description of Virtue’ and is the longest and most detailed analysis of morality in all traditional Theravadin literature. According to Buddhaghosa the function of virtue is to stop bad actions and to avoid blame and its ‘proximate causes’ are remorse and shame. Starting off on this negative note he proceeds in the same manner for a full fifty eight dry-as-dust pages in the English translation. There is hardly any mention of actually doing anything one would normally think of as being virtuous. Virtue is defined and described, its proximate causes and kammic effects are discussed in detail, but in the final analysis it is presented entirely as the avoiding of bad rather than the actual doing of anything good.”

Carl Stimson:

But wait, one might ask, weren’t you just criticizing Theravada for an excess of giving? Even if wasteful, isn’t this the opposite of a “negative and selfish tendency”?

Carl Stimson, an infrequent visitor to Southeast Asia for Dhamma purposes for the last ten years, offers this review of Shravasti Dhammika’s book The Broken Buddha.

Carl Stimson:

I have long seen this religion as the most faithful representative of the Buddha’s teachings.

The book is at turns angry, funny, cutting, astounding, and, unfortunately, sometimes poorly researched. For some, Bhante Dhammika’s casual relationship with facts and tendency toward generalization may limit their ability to take the thrust of his arguments seriously.

Bhante Dhammika’s critiques of Theravada appear to fall into four main categories: problems with rules, wasteful giving, negativity/self-centeredness, and the poor treatment of women.

He argues that Theravada has taken simple and uncomplicated guidelines for lay and monastic conduct laid down by the Buddha and turned them into suffocating rules that are either taken to extreme, ignored completely, or broken using sneaky loopholes and tricks of logic, and that Commentarial interpretation is often found when one seeks the root of a problem.

He gives many examples from his long years in robes to illustrate these tendencies. Many of the most absurd and humorous of these involve the Vinaya. For instance, “handling money” (in Pali, ‘gold and silver’) is often the focus of criticism.

The author is not critical of monks who handle money, indeed he admits to having done so himself in certain circumstances, his point being that a balanced approach is needed, one that avoids unnecessary anxiety over running afoul of extreme interpretations.

The above bolded sentence help us to recognize the reason for the agitation of S. Dhammika.

Carl Stimson:

The first category—the slavish adherence to or disregard for Vinaya—may be the easiest to dismiss as having nothing to do with “true” Theravada. Indeed, there is so much variation among Theravada monks it is difficult to make a unified critique. Burmese monks stick to rules that Thai ones ignore, and vice versa. Sri Lankan monks interpret a rule one way, Cambodian ones another. And even within countries, one sect will do one thing and others will take different approaches. Aren’t these cultural or personal differences, not problems with the foundation of the religion? Yet, the author makes a compelling case that (a) when Theravada goes too far, it is often because it is following the minute stipulations given in the commentaries rather than the simpler guidelines given by the Buddha, and (b) Theravada has a strong tendency to value tradition and culture over the Buddha’s teachings, even in the face of clear scriptural evidence.

He want to adapt Vinaya according to his wish, so that the commentaries becomes the enemy of him.

Carl Stimson:

The second category—wasteful giving—is something I believe many Western Buddhists struggle with when encountering Theravada in its native setting. … lay Theravadins give out of a desire to support the Sangha and perform wholesome deeds, thus making merit that will help them karmically in the current life and lives to come. Monks, for their part, have no real choice in the matter. They live at the mercy of lay supporters, and besides, denying an opportunity to make merit to someone with a sincere desire to give would be unseemly if not wrong. For many years, I mostly accepted this answer. It seemed to cover all the bases—one couldn’t blame the lay people because their desire to give was pure and founded in solid Buddhist logic, and one couldn’t blame the monks because they are simply vessels for the lay public’s generosity—and remaining critical made me feel somewhat culturally insensitive.

S. Dhammika is attemping to convince people what he want using arguments that even go against the Generosity which is a factor in Ten-fold Sammadithi.

Then S. Dhammika contradicts his own points as addressed below.

Carl Stimson:

The third category—self-centeredness—was something I had not thought of before and caused a dramatic shift in my understanding of how well Theravada puts the Buddha’s teachings into practice. The typical explanation of the difference between Theravada and Mahayana goes that the former sticks only to what was taught by Gotama the Buddha, while the latter adds teachings from other “buddhas” and spiritual figures. To the faithful, this lends Theravada an air of purity, which by implication means Mahayana teachings are somehow “polluted.” Leave it to Bhante Dhammika to burst this bubble. His fascinating contention is that Theravada has a pronounced negative and selfish tendency that ignores many things the Buddha taught. To quote the monk at length:

S.Dhammika:

“Theravada certainly has a marked negative outlook, negativity being the tendency to consider only the bad, the ugly or the deficient side of things…The first chapter of the Visuddhimagga, … There is hardly any mention of actually doing anything one would normally think of as being virtuous. Virtue is presented entirely as the avoiding of bad rather than the actual doing of anything good.”

But wait, one might ask, weren’t you just criticizing Theravada for an excess of giving? Even if wasteful, isn’t this the opposite of a “negative and selfish tendency”?

Not only that, S. Dhammika has attempted to despise Visuddhimmagga in every possible way even by saying that venerable Buddhaghosa didn’t believed in his own work.

See here for this regard: Colophons of Visuddhimagga - Not By Buddhaghosa Thera