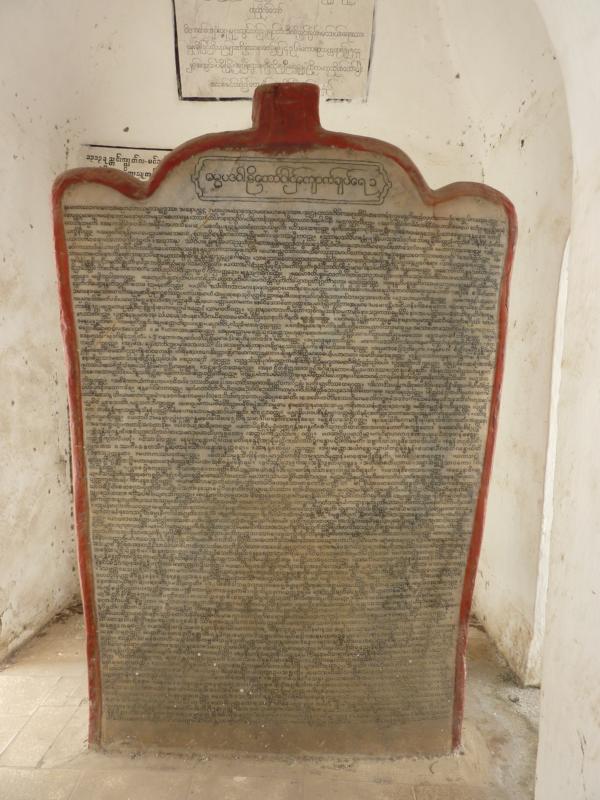

From 1853 to 1878, it was King Mindon who ruled Burma. He presided over the Fifth Buddhist Council and commissioned the Kuthodaw Pagoda, including its renowned stone engravings.

It [the Kuthodaw Pagoda] was completed in 1868. The text contains the Buddhist canon in the Burmese language.

There are 730 tablets and 1,460 pages. Each page is 1.07 metres (3+1⁄2 ft) wide, 1.53 metres (5 ft) tall and 13 centimetres (5+1⁄8 in) thick. Each stone tablet has its own roof and precious gem on top in a small cave-like structure of Sinhalese relic casket type called kyauksa gu (stone inscription cave in Burmese), and they are arranged around a central golden pagoda.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tripi%E1%B9%ADaka_tablets_at_Kuthodaw_Pagoda

Here is a photo of some of those engravings:

Like the Kuthodaw Pagoda, the nearby Sandamuni Pagoda features stone slabs engraved with the Vinaya Piṭaka, Sutta Piṭaka, and Abhidhamma Piṭaka—but it also includes the Commentaries and Sub-commentaries for each as well. Despite this, its slabs are not recognized as the ‘World’s Largest Book,’ unlike those at the Kuthodaw Pagoda.

There is, unfortunately no corresponding entry for the rock-carved books at the nearby Sandamuni Pagoda, which contains not just the Tipitaka, but the commentaries and sub-commentaries as well. How it is that the former is classed as the World’s Largest Book and not the one at the Sandamuni is a mystery.

https://photodharma.net/Myanmar/Kuthodaw-Sandamuni/index.htm

Aṭṭhakathā slabs at Sandamuni:

Just what is contained at the Sandamuni Pagoda?

. These stone slabs are:

- (a) Vinaya Pitaka - 395 slabs

- (b) Sutta Pitaka - 1207 slabs

- (c) Abhidhamma Pitaka - 170 slabs

- In [a] seven acre … compound there are:

- 248 pagodas housing a single slab each

- 139 pagodas housing three slabs each

- 72 eight-unit pagodas housing three slabs each, which altogether contains 891 slabs, and 297 four-pillared pagodas housing three slabs each which contain 891 slabs.

All these pagodas are made of brick and called Dhammazedis. These pagodas contain records of [the] Buddha’s teachings.

These stone slabs are perfectly readable today, and will be for a very long time, barring their [intentional or unintentional] destruction.

It’s amazing to think that stone-carved inscriptions can endure, legible and unyielding, for more than ten thousand years—a testament to their timelessness. Another amazing example from antiquity (this one non-Buddhist) is the Narmer Palette, discovered in Nekhen, Egypt (which was also known as Hierakonpolis; Greek: Ἱεράκων πόλις, meaning City of Hawks or City of Falcons), which is over 5,200 years old:

The Narmer Palette, also known as the Great Hierakonpolis Palette or the Palette of Narmer, is a significant archaeological find, dating from about the 31st century BC, belonging, at least nominally, to the category of cosmetic palettes. It contains some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscriptions ever found. The tablet is thought by some to depict the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the king Narmer.

Cuneiform tablets can last for an extremely long time as well, though not exactly as long as stone tablets (in best-case scenarios, stone tablets last 10,000+ years, while fired-clay tablets last up to 5,000+ years).

Below is an interesting example of still extant clay tablets from the ancient world:

Over 30,000 clay tablets covered in cuneiform writing were found in the ruins of Nineveh (Iraq), the capital of the Assyrian King Ashurbanipal’s (668–631 BC) empire.

The Library was excavated between 1851 and 1932 and a selection of tablets from the Library is on permanent display in Room 55. Despite texts from the Library having been central to the modern study of Assyrian and Babylonian scholarship for almost two centuries, we still know surprisingly little about the Library itself. Researchers have concentrated on studied parts of the Library. Less attention has been paid to what was in the Library as a whole, or what the Library was for.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/projects/what-was-ashurbanipals-library

The above-described tablets are not only perfectly legible today, but many at the British Museum are now being translated for the first time in history.

A little research conducted with the help of AI informs me that, in best-case scenarios, stone tablets can last for 10,000+ years, cuneiform fired-clay tablets for 5,000+ years, palm-leaf manuscripts for 500–1,000+ years if stored in dry, dark, and pest-free conditions, and 100–300+ years in normal Southeast Asian conditions, leather-bound books for 1,000–1,500+ years under perfect conditions and 300–500+ years in normal circumstances, hardcover books 100-300+ years under normal circumstances (up to 500 under the best conditions), softcover books for 50–100+ in normal circumstances (up to 200+ years under the best conditions), and finally e-books, pdf files, etc., rely on servers and hard-drives, which themselves rely on a great deal of fragile infrascture (electrical grids, networks, etc.), and are therefore very unreliable.

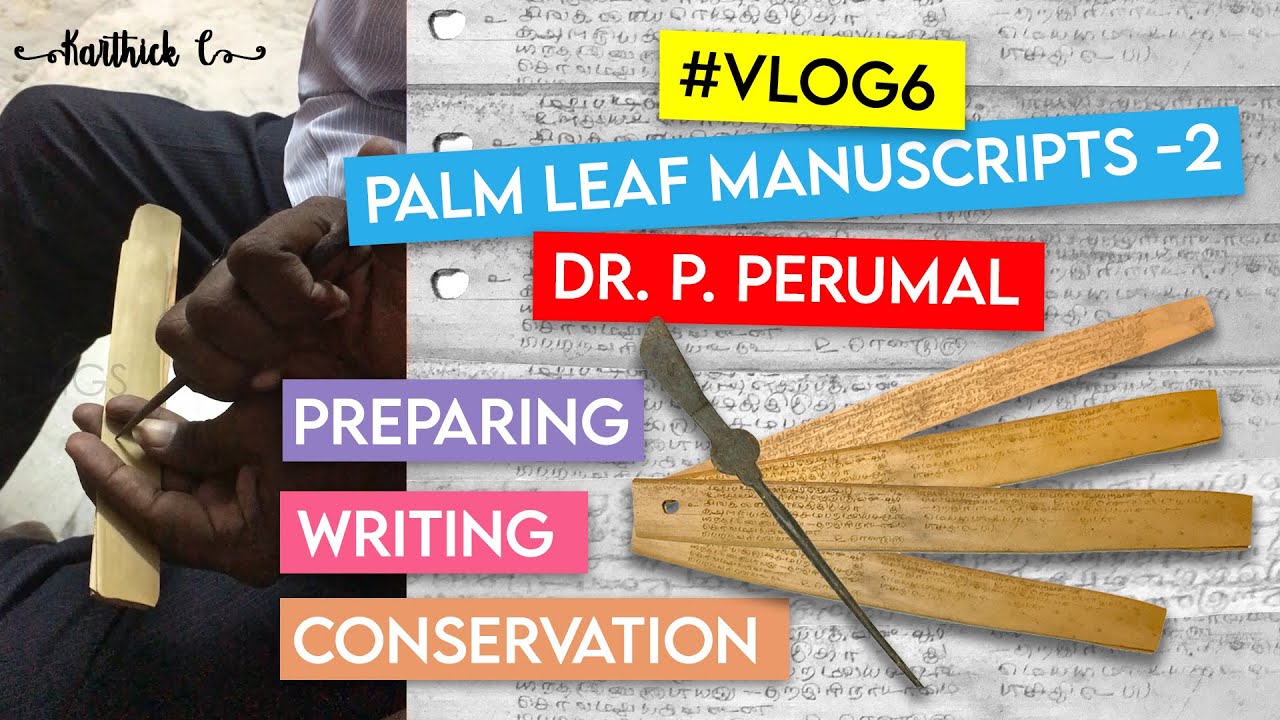

As we can see, stone and then clay tablets last the longest by far, and there is very little doubt that Buddhist Kings in the future will construct more of them, in the tradition of Asoka and Mindon, etc., given the opportunity. Historically, however, the most frequently used medium for creating Buddhist texts in Southeast Asian countries has been palm-leaf manuscripts.

Paper was not commonly produced in pre-colonial Southeast Asia for a number of reasons. One being the high humidity. Paper molds quickly in tropical climates. Palm leaves resist decay better when oiled. Another was the extensive monsoon rains. Excessive flooding could easily destroy paper stores. Palm-leaf manuscripts were also cheaper to produce locally, without any complex paper-making infrastructure needed to create them. Paper making was also more labor-intensive.

There was some limited amount of paper production in some areas. Shan people, for example, did produce some paper. But the majority of the paper that reached Southeast Asia was bamboo paper imported from China, which was very expensive and had to be acquired via maritime trade.

So palm-leaf manuscripts (which are made from dried and treated palm leaves and can last up to 1,500+ years in the best-case scenario, but usually last 100 to 300+ years in Southeast Asian climates) have traditionally been the primary form of text used to preserve the Dhamma in Southeast Asian Buddhist countries, and due to the challenges with making and acquiring paper, if Western civilization does fall (as was discussed here), it is very likely that Southeast Asian monks will go back to preserving the Buddhist texts via the creation of palm-leaf manuscripts again, rather than modern-style printed soft and hardcover books.

That is why it is very important to realise that the skills needed to produce them (which have been increasingly in decline since the introduction of the Western printing press) need to be preserved.

Here is some information from the Wikipedia entry on palm-leaf manuscripts:

Palm-leaf manuscripts are manuscripts made out of dried palm leaves. Palm leaves were used as writing materials in the Indian subcontinent and in Southeast Asia dating back to the 5th century BCE. [1] Their use began in South Asia and spread to other regions, as texts on dried and smoke-treated palm leaves of the Palmyra or talipot palm. [2] Their use continued until the 19th century when printing presses replaced hand-written manuscripts.[2]

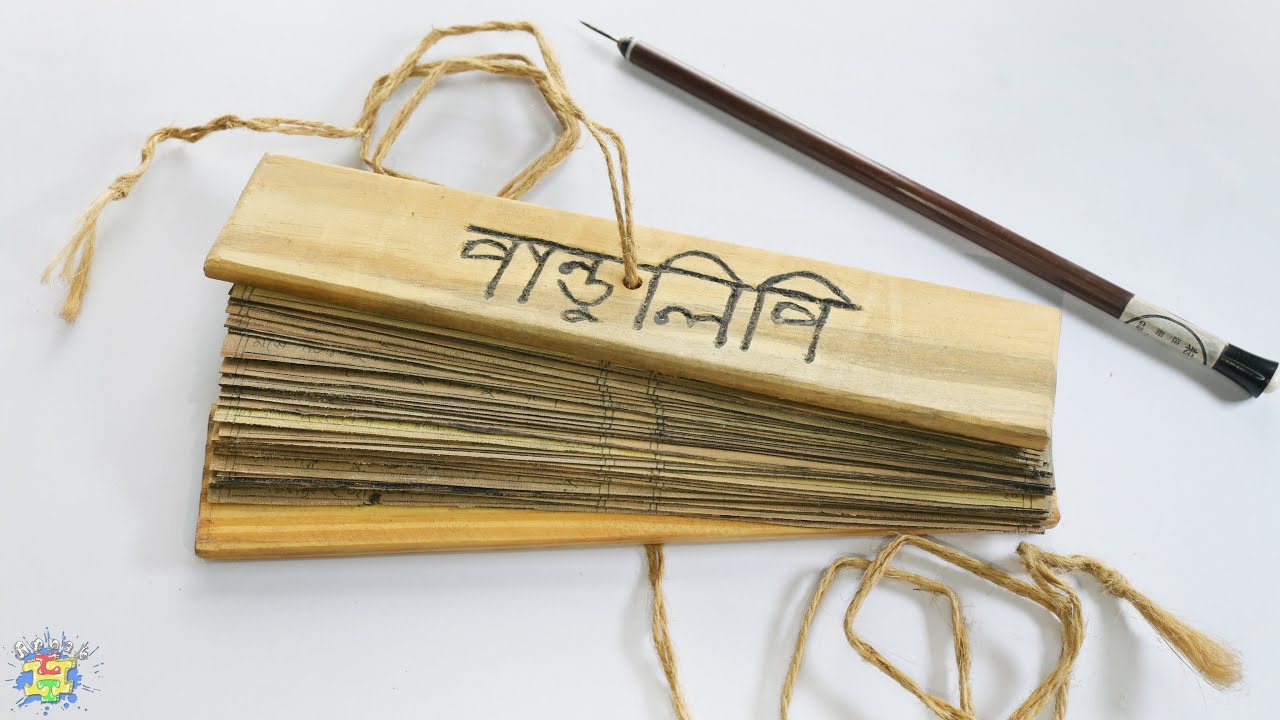

In Myanmar:

In Myanmar, the palm-leaf manuscript is called pesa (ပေစာ). In the pre-colonial era, along with folding-book manuscripts, pesa was a primary medium of transcribing texts, including religious scriptures, and administrative and juridical records.[20] The use of pesa dates back to 12th century Bagan, but the majority of existent pesa date to the 1700-1800s.[20] Key historical sources, including Burmese chronicles, were first originally recorded using pesa.[20][21] The Burmese word for “literature”, sape (စာပေ) is derived from the word pesa.[20]

In the 17th century, decorated palm leaf manuscripts called kammavācā or kammawasa (ကမ္မဝါစာ) emerged.[21] The earliest such manuscript dates to 1683.[21][22] These decorated manuscripts include ornamental motifs and are inscribed with ink on lacquered palm leaves gilded with gold leaf.[21] Kammavaca manuscripts are written using a tamarind-seed typeface similar to the style used in Burmese stone inscriptions.[21] Palm-leaf manuscripts continued to be produced in the country well into the 20th century.[23]

Renaldo