How did white-clothed lay people dress in the past? I don’t think t-shirts existed back then. Did they dress similar to monks but in white robes or cloths?

I imagine white robed just meant they were in nice clothes - the way people dress these days when they go out?

Even nowadays, lay people wear white clothes when observing the 8 precepts. I’m just curious as to how lay people from the past dressed because if they wore white robes in a similar manner as monks, I would love to do that too.

I do remember reading somewhere that the clothing style in the past was similar to monks. People would wear robes and leave one shoulder open or something like that.

Hi HappinessSeeker,

The term Odātavasana (‘white-clad’) is employed to denote householders, as the wearing of white cloth distinguished them from monastics in saffron robes.

Some minor disagreement may arise on this point: while some view it as a guideline requiring the use of white and maintain that it should be uniformly adopted, others regard it as a distinct category of commitment. You will observe variation among Buddhist countries in this regard.

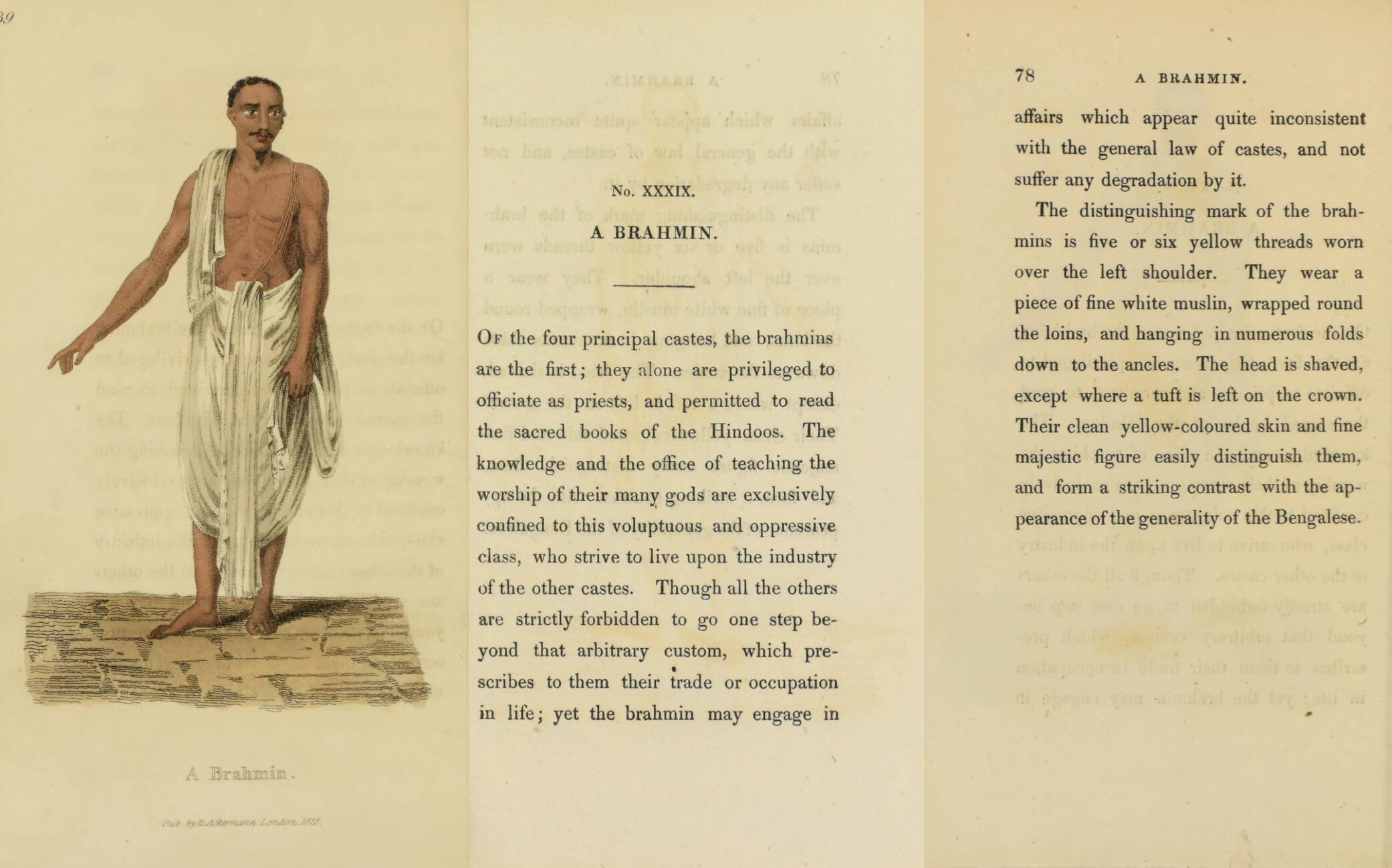

The design of the Ascetic’s robe differs from that of laypeople; therefore, the assumption that this particular design—along with its specific color—was uniformly adopted is implausible. The upper classes of Indian society, represented by the Brahmins, adhered to wearing plain white garments, making it easy to mistake them for ordinary people.

Thus, even when wearing white, the design of their clothing would differ from that of monks and other devout hermits.

The texts offer no precise information on garment design; what is evident is the Lord Buddha’s emphasis on modest, simple clothing, with appropriate coverage and arrangement for both men and women, as modesty and chastity are key components of Buddhist ethics.

Hello,

Thank you for your response.

I looked up the phrase “robe over one shoulder” on SuttaCentral and found that brahmins, monks, ascetics, nuns, kings, princes, and even Brahmās and the king of the devas were described as arranging their robes over one shoulder on occasions. This led me to think that perhaps everyone at the time customarily left one shoulder bare, similar to monks.

The ‘one shoulder bare’ style seem to be found in other ancient cultures too so I think it’s a universal practice (also followed in the deva and Brahma worlds).

At the very least, I think lay people’s outfits share the ‘one shoulder bare’ style in common with monks.

That was not really the case within ancient Indian society; clothing was highly ornate and elaborate for the political ruling classes [far from the adoption of plain white, referring back to your original post, though the designs were diverse]. As for the Brahmins, the shoulder was sometimes left exposed, though not in the same design as Buddhist monks’ robes.

Asiatic Costumes (1802), No. XXXIX, pp. 77–78.

A quick Google search will show you some photos of Brahmins adopting this one-shouldered style. However, it is not considered formal attire; in most cases, only the lower part of the body is covered.

I believe that while laypeople’s clothing was often adorned with intricate patterns and designs, it was nevertheless styled in a way that allowed them to arrange part of the garment over one shoulder. Even the king of the devas is described in the suttas as arranging his robe over one shoulder — and given his divine status, his garments were almost certainly ornate. Yet, he was still able to leave one shoulder bare, which suggests that this gesture was widely practiced regardless of clothing style.

From what I understand, laypeople also wear white when observing the Eight Precepts (even nowadays). In the case of King Mahāsudassana, we see that he too is described as “arranging his robe over one shoulder” while observing the sabbath. So, returning to the original question of the post, I do think that the way white-clothed laypeople wore their upper garments — at least during religious observances — was quite similar to the way monks wear theirs.

On a fifteenth day sabbath, King Mahāsudassana had bathed his head and gone upstairs in the royal longhouse to observe the sabbath. And the heavenly wheel-treasure appeared to him, with a thousand spokes, with rim and hub, complete in every detail. Seeing this, the king thought, ‘I have heard that when the heavenly wheel-treasure appears to a king in this way, he becomes a wheel-turning monarch. Am I then a wheel-turning monarch?’

Then King Mahāsudassana, rising from his seat and arranging his robe over one shoulder, took a ceremonial vase in his left hand and besprinkled the wheel-treasure with his right hand, saying:

‘Roll forth, O wheel-treasure! Triumph, O wheel-treasure!’

Then Sakka went up to that spirit, arranged his robe over one shoulder, knelt with his right knee on the ground, raised his joined palms toward the anger-eating spirit, and pronounced his name three times: ‘Good fellow, I am Sakka, lord of gods! Good fellow, I am Sakka, the lord of gods!’ But the more Sakka pronounced his name, the uglier and more deformed the spirit became, until eventually it vanished right there.

SuttaCentral

“Then, bhikkhus, the Brahmā Sahampati knew with his mind the thought in my mind and he considered: ‘The world will be lost, the world will perish, since the mind of the Tathāgata, accomplished and fully enlightened, inclines to inaction rather than to teaching the Dhamma.’ Then, just as quickly as a strong man might extend his flexed arm or flex his extended arm, the Brahmā Sahampati vanished in the Brahma-world and appeared before me. He arranged his upper robe on one shoulder, and extending his hands in reverential salutation towards me, said: ‘Venerable sir, let the Blessed One teach the Dhamma, let the Sublime One teach the Dhamma. There are beings with little dust in their eyes who are wasting through not hearing the Dhamma. There will be those who will understand the Dhamma.’ The Brahmā Sahampati spoke thus, and then he said further:

SuttaCentral

Then King Pasenadi got up from his seat, arranged his robe over one shoulder, knelt with his right knee on the ground, raised his joined palms toward those various ascetics, and pronounced his name three times: “Sirs, I am Pasenadi, king of Kosala! … I am Pasenadi, king of Kosala!”

SuttaCentral

Also, I found something interesting here as well.

Robes of the following colors should not be worn: entirely blue (or green—the Commentary states that this refers to flax-blue, but the color nīla in the Canon covers all shades of blue and green), entirely yellow, entirely blood-red, entirely crimson, entirely black, entirely orange, or entirely beige (according to the Commentary, this last is the “color of withered leaves”). Apparently, pale versions of these colors—gray under “black,” and purple, pink, or magenta under “crimson”—would also be forbidden. As white is a standard color for lay people’s garments, and as a bhikkhu is forbidden from dressing like a lay person, white robes are forbidden as well.

Ch. 2 Cloth Requisites | The Buddhist Monastic Code, Volumes I & II | dhammatalks.org

White robes are forbidden for monks. If a monk wears white robes, it would be too similar to lay people’s clothing. This suggests that whenever a lay person dress in white for the sabbath/uposatha, the style is similar to monks’.

A monk doesn’t wear laypeople’s clothes (white shirt and pants) that could lead to confusion with them, and the laypeople don’t wear the monk’s ticīvara — rather, they wear white shirts and pants. So what do you mean when you say it resembles the monks’ style? (The design? — it’s not so.)

I don’t understand what exactly you’re referring to. Are you saying that laypeople used to wear clothing like monks but in white? Like this:

Or that they wore ordinary clothes with something fixed over the shoulder, like a belt (with one shoulder left bare, etc.)? Please state directly what you mean.

My point is that back then, lay people’s clothes were not shirts and pants but robe-like garments.

I don’t understand what exactly you’re referring to. Are you saying that laypeople used to wear clothing like monks but in white? Like this:

Yes. As we know, t-shirts like in modern times didn’t exist back then so I think people just wrap garments around their body, so they can easily remove the garment that cover one shoulder and put it on the other to leave one shoulder bare.

If I remember correctly, monks wear three robes: one for the lower body, and two for the upper body. The upper robe is often arranged to leave one shoulder bare, and the outer robe adds another layer when going out. Since their robes aren’t like modern shirts or pants, these layers serve to fully cover the body. In the same way, I think laypeople may have also used two or more garments to cover themselves . The inner robe cover one shoulder and the outer robe cover the other. It’s not a shirt so they need more than one garment to cover their upper body.

If it makes it easier to visualize, just look at my profile picture. Now image an outer white robe to cover the other shoulder. They can easily put the outer white robe on the other shoulder to leave one shoulder bare.

In brief, when lay people observe the 8 precepts, I think they wore white robes.

In their normal day-to-day life, their clothing may be more stylish with intricate designs, patterns and beautiful colors but not t-shirts and pants like we see nowadays. Their garments were more robe-like and they had to wrap it around their body. So, they can easily leave one shoulder bare on occasions like in the examples from suttas I shared above.

The suttas do not mention anything in that regard, so on what basis are you making such conjectures and definitive-sounding conclusions.

I wouldn’t be so quick to make a definitive claim. It seems your understanding is based on the modern, stereotypical definition of a T-shirt, which isn’t what I’m referring to. What I mean is a garment similar to what is known as a tunic—a torso-covering piece of clothing that existed in various forms across ancient civilizations.

Archaeological evidence demonstrates a nuanced understanding of textile design and garment construction in the IVC (Indus Valley Civilisation). In the terracotta model known as the Lady of the Spiked Throne, male figs. are shown wearing short, conical gowns marked by a dense series of thin vertical incisions. These are interpreted as stylized representations of stiffened or pleated cloth, indicating the use of structured textiles. This distinctive feature is absent in other terracotta figs. of comparable context, suggesting a unique or symbolic form of dress. Such artistic choices reflect both technical proficiency in textile prod. and a cultural awareness of clothing as a meaningful visual element.

“The wear a short conical gown marked by a dense series of thin vertical incisions that might suggest, in their turn, a stiffened cloth. This peculiar element of dress, as far as I know, does not appear in other terracotta figurines of the same fashion.”

— Vidale, Massimo (2011). The lady of the spiked throne, The power of a lost ritual, p. 24

These figurines are dated to Mehrgarh Period VII, which corresponds to approximately 2700–2500 BCE, situating them within the Chalcolithic period of the Indus Valley Civilization. So we are talking about roughly 20 centuries before the time of the Buddha, indicating that such cultural elements would have already been well in place by then.

Upāsakas/Upāsikās generally lead ordinary lives—engaging in sensual pleasures, holding jobs, and managing household responsibilities (They do not don ceremonial white robes; instead, they wear ordinary white garments). Anagārikās, on the other hand, take on a more renunciant role; they often live in or near monasteries, observe complete celibacy in line with eight precepts, and wear white robes that look like monastic attire (though not technically so). They devote themselves fully to Buddhist practice and are commonly regarded as a bridge between laypeople and ordained monks or nuns, actively supporting the monastic community.

Some images for review: Anagārika Ordination