[Report] Lost in Thought, By David Kortava | Harper’s Magazine

Adjust

Share

On a cloudless afternoon in March 2017, Megan Vogt drove her truck toward a Delaware town between the coastal plain and the foothills of the Appalachians. She was on her way to a silent retreat at Dhamma Pubbananda, a meditation center specializing in a practice called vipassana, which its website describes as a “universal remedy for universal ills” that provides “total liberation from all defilements, all impurities, all suffering.” Those who attend Dhamma Pubbananda’s retreats pledge to observe strict rules (no reading, no dancing, no praying) and to stay for the whole ten days, as it is “both disadvantageous and inadvisable to leave . . . upon finding the discipline too difficult.” Megan knew that she’d have to forfeit her cell phone and observe a mandatory “noble silence,” so she called her mother one last time. “I love you, I love you, I love you,” she said. “I’ll talk to you in ten days.”

On the first day of the retreat, Megan, a cheerful twenty-five-year-old with blue eyes and shoulder-length hair dyed a cardinal red, woke at four o’clock in the morning to the chiming of a bell. For a cumulative ten hours and forty-five minutes, she sat cross-legged on a rug, her spine erect, and tried to focus on her breath. During breaks, she walked among the beech trees and orange lilies on the center’s thirteen acres. That evening, everyone gathered in the meditation hall and an instructor inserted a videotape into an old VCR. On the screen was an elderly man with soft, hooded eyes, sitting cross-legged on the floor. Satya Narayan Goenka, a Burmese businessman turned guru, had taken up meditation in the Fifties, hoping to alleviate his chronic migraines, and was so happy with the results that he went on to establish a global network of more than one hundred vipassana centers. Goenka died in 2013, but students on his retreats still receive much of their instruction from grainy recordings of the master himself.

“The first day is over,” Goenka said. “You have nine more left to work.” His voice was gravelly, his demeanor almost soporific. “To get the best result of your stay here, you have to work very hard,” he said. “Diligently, ardently, patiently, but persistently, continuously.” He spoke of the difficulties students would encounter in the coming days. “The body starts revolting. ‘ I don’t like it. ’ The mind starts revolting. ‘ I don’t like it. ’ So you feel very uncomfortable.” He called the untrained mind “a bundle of knots, Gordian knots”—an engine of tension and agitation. “Everyone will realize how insane one is.” He looked into the camera with an air of sympathy. “This technique will help you,” he said. “You must go to the source of your misery.”

At the time, Megan’s life was in flux—she had just gone through a breakup and decided to move to Utah, where she planned to work on an organic farm. Ten days of meditation sounded restorative, a way of turning the page to a new chapter. She found the early days of the retreat physically challenging in the ordinary sense: she had aching knees, a sore lower back, hunger pangs. But it was nothing she wasn’t used to from her time as an AmeriCorps volunteer, maintaining hiking trails out West, or the months she’d spent camping in national parks.

On the morning of the seventh day, Megan went outside to meditate alone under a tree. She had by now logged more than sixty hours of meditation. She wasn’t sure how long she sat there. “Time had slowed down,” she later wrote. The ferns and grasses were vibrating; they were made of vibrations, just as she was. Megan felt an exquisite serenity unlike any she had ever known. Tears came to her eyes. “I was so happy. I finally knew my place in the world. I was a child of the earth and I needed to share my joy.”

But hours later, Megan’s bliss dissipated. She became tired, then drained. She lay down on her bed and could not marshal the energy to get back up. The next meditation session was starting. She felt heavy, responsible for everything that was wrong in the world. Maybe I’m holy, she thought. Maybe I was put here to heal everyone. She forced herself upright and set her feet down on the floor.

Walking into the meditation hall, Megan looked at the rows of silent meditators, their eyes closed or staring vacantly at the wall. A surge of “immense fear” coursed through her body and she found herself panicking, unable to move. “I just zoned out into space,” she wrote later. “I can’t remember where I am. Who I am. What I’m doing here.” Then a torrent of dark thoughts came rushing in: Is it the end of the world? Am I dying? Why can’t I function or move? I can hear the Buddha now. He is telling me to meditate. I can’t, I’m so confused. Is this a test? Am I supposed to yell out “I accept Jesus as my Lord and Savior?” What am I supposed to do? I am so confused.

Buddhist meditation, which began as a practice among renunciants living in monasteries, hermitages, and caves in the fifth century bc, is now a part of mainstream American culture.[*](javascript:![]() Countless books, magazine articles, YouTube videos, apps, and corporate wellness programs celebrate its benefits to our cognitive, emotional, and physical well-being. The market for meditation products and services in the United States is valued at $1.2 billion. In 2017, by one conservative estimate, some 15 percent of American adults engaged in “mental exercise to reach a heightened level of spiritual awareness or mindfulness.” Arianna Huffington captured the pop-psych view of meditation and mindfulness in an interview during the promotional tour for Thrive, her 2014 self-help book: “The list of all the conditions that these practices impact for the better—depression, anxiety, heart disease, memory, aging, creativity—sounds like a label on snake oil from the nineteenth century,” she said. “Except this cure-all is real, and there are no toxic side effects.”

Countless books, magazine articles, YouTube videos, apps, and corporate wellness programs celebrate its benefits to our cognitive, emotional, and physical well-being. The market for meditation products and services in the United States is valued at $1.2 billion. In 2017, by one conservative estimate, some 15 percent of American adults engaged in “mental exercise to reach a heightened level of spiritual awareness or mindfulness.” Arianna Huffington captured the pop-psych view of meditation and mindfulness in an interview during the promotional tour for Thrive, her 2014 self-help book: “The list of all the conditions that these practices impact for the better—depression, anxiety, heart disease, memory, aging, creativity—sounds like a label on snake oil from the nineteenth century,” she said. “Except this cure-all is real, and there are no toxic side effects.”

Unfortunately, Huffington was wrong. Although there is data supporting the positive effects of meditation, the scientific literature is murkier than some champions of the practice would like to believe, and the possibility of negative outcomes cannot be so easily dismissed. As early as 1976, Arnold Lazarus, one of the forefathers of cognitive behavioral therapy, raised concerns about transcendental meditation, the mantra-based practice then in vogue. “When used indiscriminately,” he warned, “the procedure can precipitate serious psychiatric problems such as depression, agitation, and even schizophrenic decompensation.” Lazarus had by then treated a number of “agitated, restive” patients whose symptoms seemed to worsen after meditating. He came to believe that the practice, while beneficial for many, was likely harmful to some.

One case study, from 2007, documented a twenty-four-year-old male patient who had slipped into “a short-lasting acute psychotic state” during “an unguided and intense” meditation session. He was referred to clinicians following the onset of “an acute sensation of being mentally split.” He saw vivid colors, hallucinated, and was overcome with severe anxiety. At the height of the episode, he was tormented by “delusional convictions that he had caused the end of the world” and talked of suicide. The man had experienced one previous hypomanic episode and had a history of untreated depression. The authors posited that “meditation can act as a stressor in vulnerable patients.”

Even as academic interest in meditation has mounted, with hundreds of new papers published every year, the question of adverse effects has received little attention. Most studies don’t monitor for negative reactions, relying instead on participants to report them spontaneously. But the research that does exist is not reassuring. More than fifty published studies have documented meditation-induced mental health problems, including mania, dissociation, and psychosis. In 2012, leading meditation researchers in the United Kingdom published a set of guidelines for meditation instructors, noting “risks for participants,” including depression, traumatic flashbacks, and increased suicidal ideation. Four years later, the U.S. National Institutes of Health cautioned that “meditation could cause or worsen symptoms in people with certain psychiatric problems.” Jeffrey Lieberman, the former head of the American Psychiatric Association, told me he’d seen this in his own practice. “The clinical phenomenon is real,” he said. “There’s no question about it.”

Exactly who is vulnerable to these negative effects remains a subject of debate. Some clinicians suspect that meditation can trigger such reactions only in individuals with underlying psychiatric conditions. Vinod Srihari, of the Yale School of Medicine, explained that genetics and environmental factors can come together to kindle the onset of psychosis. “For people already at risk for a psychotic disorder, to have a first break on an extended meditation retreat makes sense logically.” Lieberman posits that most cases likely involve a latent psychiatric condition that is activated by sustained or intensive meditation. These mental health crises, he believes, tend to occur in the context of a retreat, when people are meditating for hours at a time. “For most people, meditation is an either innocuous or potentially beneficial activity,” Lieberman said, “but in a small number of individuals it has the potential for psychological destabilization.”

But an alternate view has been around for decades and has recently been gaining traction. Some clinicians believe that meditation can cause psychological problems in people without underlying conditions, and that even forty minutes of meditation per day can pose risks. In 1975, The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease published the case study of a thirty-eight-year-old woman, Mrs. M., who had no history of trauma or psychotic episodes but had begun to experience “altered reality testing and behavior” soon after taking up transcendental meditation. She was meditating for twenty minutes, twice a day. The authors, psychiatrists at the University of California, Davis, wrote that

an altered state of consciousness within days after beginning TM, and the occurrence of the “waking fantasies” shortly thereafter, leave little doubt of some causal relationship between the use of TM and the subsequent psychosis-like experience.

They concluded, “We would expect the occurrence of powerfully compelling fantasies in some portion of normal individuals utilizing depressive procedures of any form,” including meditation.

Precisely what happened after Megan’s unraveling in the meditation hall is unclear. By one account, she went outside and tried to tear down a fence. By another, she broke into uncontrollable laughter. What is certain is that one of the teachers, a middle-aged woman named Yanny Hin, realized that something was wrong. Hin found a volunteer in the kitchen, Jodi Beck, and asked her whether she’d mind attending to Megan. Beck tried having a conversation with Megan but couldn’t follow her train of thought—something about God “getting back at her” for something she’d done. Megan kept asking, “Is Jesus punishing me?” Beck told me. “She didn’t understand what was happening to her.”

As she ranted, Megan mentioned that she had stopped taking her medication. She had been on the lowest therapeutic dose of Zoloft for mild anxiety since her early twenties. Before admitting Megan to the retreat, the center’s administrators required that her doctor complete a form certifying that she was in good health. One of the questions read: “If the patient has difficulty during the course would you be available to him/her?” Megan’s provider checked yes. Hin instructed Beck to administer Megan’s pills for the remainder of the retreat, but the center did not attempt to contact Megan’s doctor.

Megan spent much of the next three days in her room, trying to concentrate on sensations in her body. Beck sat by her side. “She always had the option to leave,” Beck said. “She wanted to stay. She doubled down. She was trying so hard.” According to Beck, Megan told Hin that she felt like she was going crazy. Hin instructed Megan to focus on her breath. During one meeting, Megan had trouble sitting up, so Hin had her lie down. When Megan clenched her fists, Hin told her to focus on the feeling in her hands. “Yanny had no sense of this being anything that she couldn’t teach her way out of,” Beck told me. When Megan got agitated, “the instruction was always the same: close your eyes, go back to meditating.” (Yanny Hin declined to be interviewed for this story.)

On the last evening, more than sixty hours after the conspicuous onset of Megan’s mental health crisis, Beck managed to get in touch with Megan’s family. “Her problems were getting worse and worse,” Beck told me. “She looked like a ghost of herself. She hadn’t slept in days. She had stopped showering.” Beck, who moonlights as a bartender, told me she recognized when someone could not get behind the wheel of a car. “She was not equipped to leave without help.”

When Megan’s parents and her younger sister, Jordan, arrived the next day, Beck asked for them to visit Megan one at a time, so as not to overwhelm her. Her mother, Kris, went in first. “That’s not confused, that’s psychotic, ” she said. “That’s not my daughter.” Jordan went in next. Megan was hunched over at the foot of the bed, staring at the ground. She looked pale. Jordan sat down on the opposite end.

“Hey, Meg.”

A moment passed in silence.

“You’re not really here,” Megan said finally.

“It’s me,” Jordan said, holding out her hand. “You can touch me, I’m here.”

“I’m creating you. You’re just a projection.”

Megan recoiled from her family and resisted getting into the car. “I have to die here,” she cried. Eventually, Hin persuaded Megan to leave with her mother and sister. Her father, Steve, followed in Megan’s truck. As they drove off, Megan’s wish to die took on a violent urgency. She clutched at her neck. She stuffed her mouth with a blanket. She attempted to climb into the front seat and get at the glove box, where she knew her mother kept a switchblade. As the car accelerated on the interstate, Megan pried open the door. Jordan held on to her and pulled it shut.

Kris called Steve and told him she was going straight to the University of Maryland’s Harford Memorial Hospital, which has a psychiatric unit. Megan screamed at her mother, “Stop talking to the devil !” Jordan took off a necklace that Megan had made for her out of redwood bark and pine nut shells. She put the necklace in Megan’s hand, “just trying to get her to feel that there was a physical reality.”

In the emergency room, Megan repeated, over and over, “I did something terrible, I did something terrible.”

“Baby, what did you do?” her mother pleaded. “We can work through this.”

“I killed the universe.”

According to hospital records, Megan appeared “disheveled and unkempt” and seemed to be “responding to internal stimuli.” Her initial physical examination was “limited, as patient is very disorganized and afraid. Doesn’t want anyone to touch her.” As medical staff were taking her vitals, Megan pulled out her IV and shoved the attending physician. Doctors then forcibly administered an intramuscular injection of Geodon, a powerful antipsychotic. Beyond her psychological distress, whatever was ailing her was also causing a physical reaction: her stomach churned, and she was both cold and perspiring. She was tested for drugs and infections that could induce psychosis; everything came back negative.

Her first night in the hospital, Megan was started on a new drug regimen: the antipsychotic Zyprexa, along with Ativan, a benzodiazepine used to treat anxiety. Two days later, Kris, Steve, and Jordan came for visiting hours. Megan told them she couldn’t remember how she had gotten there, and that her memory of the retreat was a haze, but she was otherwise lucid and in a bright, almost lighthearted mood. “I can’t believe I’m in a nuthouse,” she said, laughing. “People are going to think I’m crazy.” After they left, a doctor wrote in Megan’s chart that she “feels much better after seeing them,” but also that she could hear music playing.

After a week, Megan’s waves of psychosis leveled off. She was sleeping better and eating regularly. She said she could think more clearly and told her doctors that she was “sorry for everything.” The medical staff encouraged her to talk or write about her experience. They left her with paper and a pen. “I lost it on the seventh day,” Megan wrote. “I was on the right path. I had relinquished all things. But then I realized I had to relinquish my body too, and that is what sent me into a panic.” She believed her breakdown resulted from having “overworked my brain for three days not sleeping.”

Megan was not given a formal diagnosis but was told that she might be showing symptoms of bipolar disorder. Her Zoloft prescription was discontinued, as her doctors believed it could have been contributing to her mood swings. Megan showed no withdrawal symptoms, and was given a supply of Zyprexa and Ativan. She was advised to see a psychiatrist within the week and to seek immediate medical attention if she experienced “racing thoughts, increased rate of speech, mood lability or decreased need for sleep.” With that, Megan was released to her family in “medically stable condition without any safety concerns.”

Jordan scoured the internet for some clue as to what was happening to her sister. She found the Facebook page of an online support group called Cheetah House, based at Brown University, that provided guidance to people experiencing mental health problems precipitated by meditation. Its website featured articles from academic journals and firsthand accounts of meditation-induced medical emergencies. “I’m not exaggerating when I say that Cheetah House literally saved my life,” wrote one “ex-meditator-in-crisis.” Jordan sent a message to the group. “My sister entered into a meditation-induced psychotic state this week and I am searching for help,” she wrote. “She is completely disoriented and convinced that she needs to kill herself.” Jordan asked for her message to be relayed to the group’s facilitator, a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist at Brown named Willoughby Britton, who has become one of the foremost advocates of the view that meditation can be harmful even for people

without underlying psychiatric disorders.

Britton had started out as an avid meditator, but as a graduate student in the mid-Aughts she made an unexpected discovery. As part of her PhD research at the University of Arizona, Britton conducted a study to determine the effects of regular meditation on sleep quality. The consensus at the time was that meditation helped people sleep better, but most of the existing studies relied on self-reports. Britton was one of the first researchers in her subfield to bring subjects into the laboratory overnight, measuring their brain waves, eye movements, and muscle tension. Britton collected two hundred nights of data. As in other studies, her twelve subjects said they had been sleeping better since taking up meditation five days a week. And the data seemed to support that for the group that was meditating less than thirty minutes per day. But any more than a half hour and the trend started moving in the other direction. Compared with an eight-person control group, the subjects who meditated for more than thirty minutes per day experienced shallower sleep and woke up more often during the night. The more participants reported meditating, the worse their sleep became.

Britton’s sample size was small, but other researchers have also documented this apparent paradox—positive self-reports combined with negative outcomes. A 2014 study from Carnegie Mellon University subjected two groups of participants to an interview with openly hostile evaluators. One group had been coached in meditation for three days beforehand and the other group had not. Participants who had meditated reported feeling less stress immediately after the interview, but their levels of cortisol—the fight-or-flight hormone—were significantly higher than those of the control group. They had become more sensitive, not less, to stressful stimuli, but believing and expecting that meditation reduced stress, they gave self-reports that contradicted the data.

Until the sleep study, Britton had been, in her own words, an evangelist for meditation. “I just sat on the data,” she told me. “I really didn’t want to see it, because it was sort of the wrong answer.” Britton filed away the results and delayed publishing them. On a vipassana meditation retreat in 2006, she told one of her instructors about her research. “The teacher kind of chastised me, like, ‘Why are you therapists always trying to make meditation a relaxation technique? That’s not what it’s there for. Everyone knows that if you go and meditate, and you meditate enough . . . you stop sleeping.’ ” Britton’s resistance to her own findings gradually gave way to curiosity. In 2010, she finally published the results of her sleep study.

Britton and her team began visiting retreats, talking to the people who ran them, and asking about the difficulties they’d seen. “Every meditation center we went to had at least a dozen horror stories,” she said. Psychotic breaks and cognitive impairments were common; they were often temporary but sometimes lasted years. “Practicing letting go of concepts,” one meditator told Britton, “was sabotaging my mind’s ability to lay down new memories and reinforce old memories of simple things, like what words mean, what colors mean.” Meditators also reported diminished emotions, both negative and positive. “I had two young children,” another meditator said. “I couldn’t feel anything about them. I went through all the routines, you know: the bedtime routine, getting them ready and kissing them and all of that stuff, but there was no emotional connection. It was like I was dead.”

Britton realized that she had experienced some of the symptoms that her interview subjects were describing. “It took me three years of trauma training to realize, oh, that’s dissociation. And I hadn’t realized it because if you can sit for long periods of time and not feel any pain and not have any thoughts, most meditation teachers are going to say that you’re doing great,” she said. “But this was different. I felt like I was living in a parallel dimension from the rest of the world, not connected at all.” She recalled one experience she’d had while still in graduate school. “I was meditating outside, and I felt something shift. I was having a really hard time, and then everything just clicked.” Suddenly everything seemed fine. “Now I know that’s a red flag, when someone goes from having intense negative emotions to instantly feeling fine, as if someone just flipped a switch.”

In 2017, Britton and her team published their findings in PLOS One, a prominent scientific journal. The report presented a taxonomy of “meditation-related difficulties,” including anxiety and panic, traumatic flashbacks, visual and auditory hallucinations, loss of conceptual meaning structures, non-referential fear, affective flattening, involuntary movements, and distressing changes in feelings of self. Some of the study participants were new to meditation, but nearly half had at least ten thousand hours of practice. The majority of the sample—forty-three out of sixty meditators representing Theravada, Zen, and Tibetan traditions—had experienced moderate to severe impairment in their day-to-day functioning. Ten had required inpatient hospitalization. “Hearing those stories, one after the other, I was like, wow, there’s a lot of suffering here,” Britton said. “That study changed everyone who worked on it. I just couldn’t be the evangelist that I had been.”

Some of the individuals in the study had preexisting psychiatric conditions, but most did not. For Britton, the takeaway was that adverse effects routinely occur even under optimal conditions, with healthy people meditating correctly under supervision. “It’s so easy to assign a latent vulnerability after the fact,” Britton said, “but we are seeing people who really had no indicators.”

While Jordan waited for a response from Britton, Megan sought her own answers from the instructors at Dhamma Pubbananda. “Something very profound happened to me during the course,” she emailed the center staff.

I have memory loss; there is about a week gone during and after the retreat that I cannot remember/is very fuzzy. I am now trying to get back to my normal life, but I am having some trouble focusing; my mind keeps going back to the retreat and trying to figure out what happened.

Megan wondered whether there were lessons from Buddhism that could “shed light on my situation.” She asked whether Yanny Hin might be available for a phone call, and apologized for any disturbance she may have caused. A volunteer named Arun, whom Megan had never met, wrote back that day: “Hi Megan, Forwarded your email to Hin. Take care of yourself. With Metta.”

The Buddhist ascetics who took up meditation in the fifth century bc did not view it as a form of stress relief. “These contemplative practices were invented for monastics who had renounced possessions, social position, wealth, family, comfort, and work,” writes David McMahan, a professor of religious studies at Franklin and Marshall College, in a 2017 book, Meditation, Buddhism, and Science. Monks and nuns sought to transcend the world and its cycles of rebirth and awaken in nirvana, an unfathomable state of equanimity beyond space and time, or at least avoid being reincarnated as a mountain goat or a hungry spirit in the hell realm underground. In the Pali suttas, the earliest Buddhist texts, the Buddha discusses meditation almost exclusively with audiences of followers ready to reject all earthly belongings. “Generally meditation is presented as something monastics aspiring to full awakening do,” McMahan writes, “an activity that is part of a way of being in the world that is ultimately aimed at exiting the world, rather than a means to a happier, more fulfilling life within it.”

In other words, mindfulness was not invoked to savor the beauty of nature or to be a more present, thoughtful spouse. According to the Pali suttas, the point of meditation was to cultivate disgust and disenchantment with the everyday world and one’s attachments to people and things. Aspiring Buddhas were “asked to contemplate the body from head to toe, inside and out,” McMahan writes, “not for relaxation and even less for body acceptance, but to bring to full realization its utter repulsiveness, coursing as it is with blood, phlegm, and pus.” If meditation conferred any practical benefit, it was in helping ascetics “accept the discomfort of a hard bed and a growling stomach or in preventing them from being beguiled by physical beauty.”

Reports of disturbing experiences during meditation appear in a number of early Buddhist writings. In the Theravada tradition, from which S. N. Goenka’s system derives, meditators are said to experience “corruptions of insight” that, from the vantage of modern clinical psychology, resemble psychosomatic ailments, including manic bliss states, gastrointestinal issues, and visual hallucinations. Monks in the Zen tradition may encounter “diabolical phenomena,” which are characterized by involuntary movements and frightening mental imagery. Chinese and Japanese Zen masters are said to succumb to a “meditation sickness” in which the afflicted become disoriented and have trouble regulating their body temperatures and energy levels. Buddhist monastics in Tibet may develop “wind illness,” the symptoms of which include confusion and agitation; according to a twelfth-century Buddhist medical treatise, the disorder is caused by the “three poisons of attachment, hatred, and closed-mindedness.”

The adoption of meditation by the Buddhist laity in Southeast Asia began during the 1880s. In British-occupied Burma, the state ceased to provide funding to monasteries, and Christian missionaries did their best to convert lay Buddhists. Against this backdrop, a young monk named Nanadhaja—determined to save meditation, and Buddhism more broadly, from erosion—took to teaching vipassana meditation outside the monasteries. For the next seventy years, the esoteric practice slowly spread among the Buddhist laity. S. N. Goenka was among the first to teach meditation to non-Buddhists, stripping the practice of its religious lineaments and rituals. Gone was the cosmology of hell realms and hungry ghosts and karma and rebirth. Gone was the promise of miraculous healing and mind-reading and flying that meditation was believed to enable. Gone, too, was the open acknowledgment of the sundry mental and physical tribulations that might surface in the course of a serious meditation practice. Most difficulties triggered by meditation were seen as temporary, even an indication of progress, and meditators were encouraged to keep going.

Back at home, Megan continued to meditate, often for hours at a stretch, oscillating between lethargy and panic. Kris took medical leave to attend to her daughter full-time. She contacted a number of psychiatrists who she thought might be able to help. She drove Megan to her scheduled appointments, but Megan wouldn’t get out of the car; she kept a total of four appointments in two months. Every morning Kris checked to make sure Megan had taken her Zyprexa. “The pills weren’t doing anything,” Kris told me. “They just made her sleepy.” The prescription eventually ran out, and Megan refused to see a doctor to refill it.

Megan had always kept a tidy journal, but now her writing became compulsive. She scribbled her most personal thoughts on whatever happened to be around. Kris and Jordan would find Megan’s notes on receipts, bank statements, and other random scraps of paper scattered throughout the house:

The world will go on without you. It’s been around for six billion years. Stop being so selfish.

I’m afraid my energy is going to hurt everyone else.

I can’t stay inside of the lines, I can’t stay inside of the lines.

On the morning of June 6, 2017, Megan told her parents that she was going for a walk in the park. Her eyes were bloodshot and she looked as though she hadn’t slept. She had spent the previous night in a tree house that Steve had built for the girls when they were little. Before falling asleep, Steve had made sure his guns were accounted for and locked up. That morning, as soon as Megan drove away, he got a bad feeling. “We gotta go looking for her,” Steve told Kris. They drove to the park, a small wooded area along the Mason-Dixon Trail near their house, but Megan’s truck wasn’t there. They decided that Steve would wait for Megan at home while Kris continued to search on her own. After dropping Steve off at the house, Kris drove north along River Road until the Norman Wood Bridge came into view, standing one hundred and twenty feet above the rocky banks of the Susquehanna. Kris saw a scrum of police cars with their lights flashing, and Megan’s truck, parked just ahead. “I just knew,” she said. In her truck, Megan had left a note for her family: “I couldn’t keep running from what was supposed to have happened. If you get a chance to die—take it.”

Today, the luminaries of mainstream Buddhism widely promote meditation to laypeople, and refuse to acknowledge that it carries any risks. In 2012, at a conference on mindfulness at the Mayo Clinic, Britton presented her early findings on the potential adverse effects of meditation to the Dalai Lama. “The science of meditation has pretty much exclusively focused on the positive effects of meditation,” Britton said. “But if we want to understand the entire trajectory of the contemplative path and everything that that entails, we need to be more evenhanded and more balanced in our investigations, and begin to investigate the full range of experiences, including the ones that would be considered negative, difficult, challenging, or maybe even problematic.”

In a recording of the proceedings, the Dalai Lama can be seen nodding gravely, smiling genially, and, on several occasions, interjecting to crack a joke, such as suggesting that he himself might one day end up with such impairments. At one point, he said, “These people, I think they just hear things and then develop some sort of excitement.” He said that these meditators needed to read more books, analyze what they’d read, develop firm convictions, and only then try to meditate. If they followed this course, he didn’t think there was any danger. The Dalai Lama cheerfully concluded that “these negative sides are their own mistake—the positive things, that’s the real truth.” He encouraged Britton to do more research.

Britton’s more radical conclusions are also met with skepticism in some corners of mainstream psychiatry. I asked Lieberman, who is now the chair of psychiatry at Columbia University, if it could be possible, under the right conditions, for otherwise healthy individuals to be harmed by meditation. He said he didn’t think so—that it required a preexisting vulnerability. “It may be that some individuals are susceptible and others much less,” he said, “but I don’t think meditation by itself can cause this.”

I put the same question to Matcheri Keshavan, a neuroscientist and psychiatrist at Harvard Medical School. He thought it was possible. There are reliable ways to induce psychosis and other disturbances in a healthy subject—via drugs, sleep deprivation, and prolonged confinement or isolation. “If you deprive the brain of normal inputs—through sensory or social deprivation—that can produce psychosis,” he said. “And you can think of prolonged meditation as a form of deprivation.” The brain is accustomed to a certain amount of activity. When you’re sitting motionless with your eyes closed for ten or more hours a day, he said, neurons can start firing on their own, unprompted by external stimulation, “and this might lead to unusual phenomena, which we call psychosis.”

Britton’s research was bolstered last August when the journal Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica published a systematic review of adverse events in meditation practices and meditation-based therapies. Sixty-five percent of the studies included in the review found adverse effects, the most common of which were anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment. “We found that the occurrence of adverse effects during or after meditation is not uncommon,” the authors concluded, “and may occur in individuals with no previous history of mental health problems.” I asked Britton what she hoped people would take away from these findings. “Comprehensive safety training should be part of all meditation teacher trainings,” she said. “If you’re going to go out there and teach this and make money off it, you better take responsibility. I shouldn’t be taking care of your casualties.”

Britton didn’t see Jordan’s message about her sister’s condition until it was too late, but she has since reached out to the family. Kris and Steve feel strongly that Megan would still be here, and still be herself, had she not gone on that retreat. “I do not believe that Megan was any different from you or me or anybody in America who struggles through life,” Kris told me. “Anybody locked in their mind with silence and no communication could go to those dark places.” As far as she could tell, Megan was a happy, resilient person until the retreat. “I don’t believe you have to have an issue to have occur what happened to Megan,” she said.

In my conversations with Jordan, she found it difficult to speak chronologically about what happened to her sister. “Megan showed us so many different parts of herself over those two months,” she said. “Even when she was sick, there were moments where it felt like we were sharing in the healing, not just us taking care of her.” On the last night of Megan’s life, Jordan had climbed up the creaky wooden ladder and joined her sister in the tree house; she’d brought her some herbal tea. Megan told Jordan about a memory from the retreat that had returned to her. On the final day, she said, she found herself in the presence of a bright white light, which she knew to be God, but she became scared and turned away. She said that in that moment she had to choose between heaven and hell, and that she made a mistake, and now she was trapped in hell and needed to die to escape. Jordan tried to find the words that could penetrate the fog of delirium that enveloped her sister. “Heaven and hell are not permanent ideas,” Jordan said to her. “You can choose, this very moment, that you’re not trapped in there.”

Jordan isn’t sure whether meditation caused her sister’s psychotic break or just triggered the inevitable. “I don’t think it’s out of the question that she might have had a disorder,” she said. “But it’s also possible that this wouldn’t have happened if she hadn’t gone on that retreat.” Jordan’s irresolution stemmed, in part, from her wish to honor Megan’s own understanding of what she was going through. “Megan never blamed the meditation and she never saw it as a medical problem,” Jordan said. “For her, it was a spiritual crisis.”

# When Buddhism Goes Bad

### How My Mindfulness Practice Led Me To Meltdown

Jul 16, 2021 [34](javascript:void(0)) 56

One snowy evening in the mountains of North Carolina, I snuggled into bed on the second night of a Buddhist meditation retreat. I was exhausted, and lay alone in my tiny cabin, longing for nourishing sleep. It didn’t come. My body was strangely restless, and despite being cocooned in a mound of blankets, I was still cold.

The type of meditation I had been practicing was jhana , a deep state of absorption concentration said to be essential in the Buddha’s awakening. All day I had been concentrating on my breath and scanning my body for various sensations. I had 13 days ahead of me to work, with the goal of experiencing highly refined states of awareness — and perhaps something beyond.

As I lay there musing in the brisk darkness, I suddenly sensed a tightening inside me. It was as if I was being ever so gently wound. Then quickly, the pressure intensified, and I breathed in rapid-fire staccato and violently shook. I was a guitar string being tuned beyond its highest range. The string popped. A spike of fear slashed through my guts. And that’s when I split apart.

The next four hours were a hellscape of terror, panic and paranoia. There were almost no thoughts, only my body begging to escape my skin, convulsing like a fish fighting for life. The fear was a bottomless trench.

I knew nothing, except that something, everything, was terribly wrong. For minutes, I was completely immobilized. And even when I regained control, I was incapable of finding help. I wasn’t sure if I was real, or if the door to my cabin was real, or if anyone outside of it would be real.

I punched myself in the head at one point just to feel something solid. I couldn’t help myself because I couldn’t locate myself. Where was I? Who had I become?

Finally, after hours, the attack smoldered and I drifted off. It was the worst night of my life.

The next morning, while making coffee, I stared at the creamer for two minutes, paralyzed. Hours later, I stood motionless on a windswept bluff, observing myself from somewhere above my right shoulder, stuck like a broken-down car on the shoulder of the road.

I relayed my experiences that afternoon to the two teachers who were overseeing the retreat of about 40 meditators. They were both kind, compassionate, and welcoming, suggesting various ways that I might alter my meditation practice to alleviate my symptoms

The problem, I explained to them, was that I couldn’t stop being mindful or aware of everything that was going on within my mind and body, and the awareness felt like it was choking me to death. After a day of trying alternative meditation approaches, I left the retreat.

I was crushed and bewildered during the 90 minute Lyft ride to my sister’s house in Knoxville. There, I spent a week trying to recuperate in her basement, watching reality TV and wrestling on the floor with my tiny nephews. A week later I drove back home to New Orleans, but unfortunately the effects of the retreat didn’t stay behind.

What happened to me that night may sound exotic, bizarre, psychotic and unusual, but it’s actually more common and predictable than many people think. As meditation practices have exploded in popularity in the West, they have brought with them an array of adverse experiences far beyond the typically-billed benefits of lower stress, decreased anxiety and reduced pain. The terrain of fractured, disruptive and altered states of consciousness has often been explored in Buddhist teachings through the centuries, but when these practices made their journey into Western culture, a sufficient understanding of the downsides of meditation was lost in transit.

In fact, today mindfulness meditation is primarily used as an off-label treatment for mental health issues, a strange and tortuous journey for a technique that was for centuries practiced by Asian Buddhists for achieving liberation and therefore avoiding re-birth. This rebranding, which has mostly whitewashed negative experiences of meditation and framed it as in alignment with Western mental health goals, has created a booming business of retreat centers, courses, instructors, consultants and apps. According to a 2017 report by Marketdata Enterprises, the U.S. meditation market is predicted to grow to 2 billion dollars by 2022.

I knew most of this previous to my disastrous retreat.

As an instructor in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), I spent four years teaching meditation as a full-time job. A longtime meditator, I have logged roughly 4,000 hours of practice over 10 years, including more than 100 days on roughly a dozen silent meditation retreats. I’m extremely knowledgeable of both Buddhist and secular frameworks of meditation, have read countless books on the subject, and have taken instruction from numerous renowned Western meditation teachers.

Prior to this retreat, I was an unabashed evangelist for mindfulness. I credit meditation with precipitating numerous positive changes in my life. It made me less reactive, helped me form better relationships and assisted me in curbing my drinking. It opened me up to a deeper understanding of my mind and perhaps, most important, gave me a craft and a framework through which I found meaning and purpose in my life.

But 14 months ago, my meditation practice brought me to my knees.

In the months after the retreat, I suffered from symptoms diagnosed by a therapist as post-traumatic stress disorder. I frequently experienced involuntary convulsions and simple tasks like cooking a meal induced panic attacks. I was occasionally so overwhelmed by my bodily sensations that I was unable to speak, and sometimes had problems differentiating myself from my surroundings.

The tiniest moments of adversity, such as a traffic jam, felt like death. My body was a torture chamber, lighting me up with with panic, terror, despair, a mélange of agonizing sensations. I even carried around a green squishy ball, which I desperately clutched to prevent dissociative episodes, and I rarely left the house without Xanax in my pocket.

This terrain was fresh. I had never previously experienced a psychotic episode and have no history of mental illness besides occasional bouts of mild anxiety and depression. And I didn’t have a history of any major trauma prior to the retreat.

As I navigated life with meditation-induced PTSD, I also felt betrayed. While I had heard cursory mentions of difficulties during meditation, the primary framing had been positive. I remember clearly a senior teacher answering a student’s question of how much they should meditate.

“Well, how happy do you want to be?” he had quipped.

In fact, when I had reported convulsions and some shaking on earlier retreats, teachers never voiced concern. Most of the literature I had come across on the subject of negative experiences framed them as stages or signs that one is progressing toward awakened states. In my mind, there was never a reason to stop pursuing meditation. Over a decade, I didn’t meet a single teacher who described any situation where meditation could be damaging or should be ceased. So, I soldiered on.

But, unbeknownst to me, there was someone already sounding the alarm.

Willoughby Britton is a clinical psychologist , neuroscientist, and associate professor at Brown University. She’s also arguably the world’s expert in adverse effects of meditation.

I met her by happenstance, nine months before my disastrous retreat. She was leading a conference called “Do No Harm” in Los Angeles about adverse effects of meditation. I was there because it was the cheapest way for me to complete my teaching certification in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, and had only minimal interest in the topic at the time. The attendees, maybe 300 or so, were the intelligentsia of the American mindfulness movement: therapists, meditation teachers, neuroscientists and doctors. Many of them were quite prominent. They had made their careers evangelizing for mindfulness meditation as a science of the mind, fully compatible, if not superior, to Western ideas about mental health.

The meat of Britton’s talks was the results of a 2017 paper she co-published with her husband, Jared Lindahl, called the Varieties of Contemplative Experience1. In it, they examined distressing and functionally impairing meditation experiences of 60 Western Buddhist meditators. They documented 59 types of adverse effects in their study, including involuntary convulsions, panic, anxiety, dissociation and perceptual hypersensitivity—a far cry from the mainstream branding of mindfulness meditation as a panacea for all our woes.

Their message wasn’t particularly well received. And why would it be? The livelihoods of many in the room — including mine — rested on the fact that mindfulness was going to be the saving grace of modern discontent. Britton and her co-presenters, Lindahl and the therapist David Treleaven, were bursting the bubble to the frustration of some in attendance.

Almost every mindfulness retreat, event, talk or discussion I had previously attended involved a fusion of neuroscience, psychology, testimonials, anecdotes, poetry and meditation, all of which was patched together and synthesized to fortify the pre-eminence of mindfulness as a healing approach.

But Britton and her co-presenters were savaging much of the science as sloppy, pointing out considerable misunderstandings and weaknesses in the current body of research, challenging whether secular mindfulness programs were actually secular, and generally extinguishing a lot of the feel-good vibes one expects to imbibe at such a gathering.

At one point, a prominent author of mindfulness books stood and unleashed a roughly 10-minute rejoinder to Britton’s work. His tone grew increasingly condescending as he rambled on, promoting his own conferences and bemoaning how it was our mistaken sense of self that was leading to mass human suffering and climate change.

The author’s monologue ended with him citing the poem, “The Guest House,” by Rumi, as a model for how people might handle distressing meditation experiences. The poem, often used by meditation teachers, suggests that we should welcome in all our emotions, feelings, experiences — good or bad — the same way we might welcome a guest into our home.

Previous to his outburst, Britton had described meditators who had lost the ability to feel their bodies, lost emotions for their children and, in one particularly troublesome occasion, lost the ability to recognize the meaning of a red light.

“It might be wise to look through the keyhole before letting in whoever or whatever is on the outside,” she snapped back.

I spent my last day in Los Angeles riding on a Segway, buying legal marijuana and staring at some turtles in an on-campus pond at UCLA. I was unsettled yet intrigued by Britton’s message. Some of the adverse experiences she had described were similar to challenges I had faced. But, at this point I was a decade into my intensive mindfulness meditation practice. I was too deep to get out.

Why did I start meditating? The short answer is that in 2009 I started a fist fight in a French Quarter bar over some jambalaya, a steamy kiss, and a stray comment I didn’t take fondly. The evening ended hours later after I broke a window with my fist, misplaced my shirt, and guzzled about 16 bottles of Miller High Life. My girlfriend was not happy. I wasn’t happy. Something had to change.

That speck in time represented a constant battle I had waged over the prior decade with anger and other negative emotions. I drank too much. I occasionally smashed printers that jammed. I had volatile relationships with women. My mind wandered uncontrollably.

I was drifting into my mid-20s doing things that had felt defensible at 19, but didn’t feel OK any longer. I wanted a calmer, tranquil mind, so I found a Zen center and started dropping in for weekly meditation practice. The effect was profound and immediate. Everything slowed down in the aftermath. There was peace, space, and bliss. It was like a drug. And I immediately wanted more.

In 2011, I sat my first meditation retreat in the Vipassana tradition of S.N Goenka. I spent ten days in silence, focusing on my breath and body for 10 to 12 hours a day. It was grueling, but toward the end of the retreat I had a life-changing experience.

While meditating alone in my room, I went into full-body convulsions and observed with perfect equanimity a cannonball of grief, despair and horrific pain emerge from my gut, up into my chest and then out of my mouth. At the zenith, a cascade of images emerged from the darkness of my closed eyes, and I unleashed a blood-curdling scream while bursting into tears. It was as if I had purged a lifetime of negative emotions.

In the aftermath, I floated for months in a state free of discontent. I also began experiencing memories that felt foreign — like they weren’t mine — could observe myself sleeping, and was able to quell even the slightest bit of agitation by simply focusing my attention on it.

I felt like I had a superpower. My drinking ebbed, my anger was tempered and I was able to concentrate at a much higher level at my job. A few months later, I exited a toxic relationship and quickly made a new set of new friends. I was flourishing in numerous directions and had meditation to thank for it.

A year later, I returned for another retreat. And over the next decade, I attended meditation retreats across the country, read voluminous books on Buddhism, and even moved from New Orleans to the San Francisco Bay Area to deepen my meditation practice. I often joked that the only thing that stopped me from becoming a monk was having to sew my own robes. But, it’s mostly the truth.

As the years went by, I became a full believer in much of Buddhist doctrine, especially the idea that all suffering is the product of craving or desire. It seemed self-evident to me that if I could cultivate a non-reactive state, I could live free of discontent.

I was also impressed by the arguments made by many meditation teachers that meditation was a completely secular endeavor, which could be done without any connection to religion. It was essentially, they argued, exercise for the mind.

Yet, somewhere six or seven years into my practice, whatever progress I was making petered out. I was experiencing a growing sense of bodily agitation and began self-medicating with drugs and alcohol. Looking back, it was also during this time period that I had my first dissociative experiences, in which elements of my sense of self became separated in a way that impaired my ability to function.

It seemed like the more I meditated the worse I felt. I was desperate to find a framework to understand what was happening and hunted through meditation books for references to extended periods of distress. On my shelf, I found a book that I had owned for a while but never read. It was called “Mastering the Core Teachings of the Buddha.” The cover picture was the silhouette of a sitting meditator with hot-pink squiggly lines shooting out in all directions. The author, an Alabama emergency room physician, proclaimed himself to be fully awakened. He referred to himself as The Arahat Daniel M. Ingram.

It would be impossible to fully synthesize Ingram’s 620-page tome, so I’ll stick with what was most salient for me. At the core of Ingram’s book was a Buddhist model that described meditation progress in 16 stages, each with a consistent set of characteristics. Two of the stages jumped out at me.

One was “The Arising and Passing” state, sometimes called A & P. According to Ingram, this state includes, “powerful physical shaking and releases, explosions of consciousness like a fireworks display or a tornado, visions, and especially vortices of powerful fine “electrical” vibrations blasting up or down the spinal column and/or between the ears.”

That description was eerily similar to what I experienced on my first retreat.

Ingram went on to say that after the A & P, meditators have crossed a threshold or “point of no return.” They are now destined to plunge into what he describes as “The Dark Night,” a series of stages such as dissolution, misery, disgust, and fear.

According to Ingram, one must continue to meditate through these awful experiences until reaching a deeper state of awakening. He makes it clear that the consequences of stopping are severe.

“If they give up in the stages of the Dark Night (or any time after the A&P), the qualities of the Dark Night will almost certainly continue to haunt them in their daily life, sapping their energy and motivation, and perhaps even causing feelings of unease, depression, paranoia, and even suicidal thoughts. Thus, the wise meditator is very, very highly encouraged to try to maintain practice despite potential difficulties, to avoid getting stuck in these stages.”

As bizarre as it may seem, it’s impossible to describe how relieving this diagnosis was to me. Ingram’s book validated my experiences in a way that no meditation teacher or therapist had done. With this diagnosis in tow, the upshot of my current condition was clear to me. I was halfway to awakening. I had to make it there or I would continue to suffer. I no longer had a choice.

The second time I encountered Willoughby Britton was three weeks after my disastrous meditation retreat. I was desperate for help. My body was in constant physical agony. I was struggling to make eye contact with my wife. Driving a car was becoming challenging. My left shoulder felt electrified and was uncontrollably convulsing. I was scared and didn’t know what to do.

Britton runs an organization called Cheetah House, through which she counsels meditators in distress. She’s also had adverse experiences herself. We met over Skype. I was despondent as I described my symptoms to her and she meticulously took notes. Then, Britton told me something that infuriated me. It made me want to knock someone’s teeth out. She said that many of the leading figures in the world of mindfulness meditation have had experiences like mine, but they just don’t talk about them. It’s an open secret of sorts.

“What kind of fucking person could go through something like this and not warn other people!” I yelled. When I did this, I gestured frenetically with my right hand, like I was karate chopping the air in front of me. It was the first time in years I had dropped my Buddhist pretense and allowed myself to be truly angry.

I told Britton everything that happened at the retreat and also in the months before. I explained, that motivated by Ingram’s book and similar texts, I had been meditating two hours a day if not longer. I described how on numerous occasions all my thoughts disintegrated and I bathed for extended periods of time in states of deep, non-conceptual bliss. I thought awakening was right around the corner and now feel broken and betrayed, I said.

Britton explained to me that it’s likely that my meditation practice, specifically the constant attention directed toward the sensations of the body, may have increased the activation and size of a part of the brain called the insula cortex.

“Activation of the insula cortex is related to systemic arousal,” she said. “If you keep amping up your body awareness, there is a point where it becomes too much and the body tries to limit excessive arousal by shutting down the limbic system. That’s why you have an oscillation between intense fear and dissociation.”

She suggested I try a trauma therapy called Somatic Experiencing and invited me to her support group for meditators who have experienced acute distress. Their stories were validating yet heartbreaking: a steady stream of individuals using meditation in a search for relief from suffering and instead finding greater anguish.

While some were veterans of numerous meditation retreats, others simply dabbled with a meditation application. One woman, a clinical mental health worker, ended up in a psychiatric facility after her doctor recommended she participate in a 10-day meditation retreat. Numerous participants developed problems after using Sam Harris’s popular Waking Up app.

One might wonder if these wounded meditators had preexisting conditions that triggered these experiences. Most of us don’t, a finding similar to Britton and Lindahl’s study, which reported that 57% of practitioners suffering adverse effects didn’t have a trauma history and 42% had no psychiatric issues at all prior to meditation practice.

What we do share is a feeling that’s common among those who have had traumatic experiences: neglect, shame and a sense of being unheard by those in power. Case in point, the words and work of the neuroscientist Richard Davidson.

Davidson’s and journalist Daniel Goleman’s 2017 book, “The Science of Meditation”, spent almost 300 pages documenting the positive effects of meditation. When it came to negative effects, the authors dedicated two pages.

part 2 dan lawton In a 2019 Vice article, Davidson suggested that those who have meditation-related difficulties simply aren’t meditating correctly.

“I think that many of the people who are having difficulty and who are reporting that their problems are exacerbated by meditation are not meditating correctly, to put it simply and coarsely," he said, "Some might even say that they’re not meditating. That they think they’re meditating, but they’re not really meditating.2”

His notion, contradicted by historical and contemporary accounts, is a fusion of victim-blaming and fundamental attribution error. Unable to entertain the possibility of deficiencies in the mechanism, he blames the meditator.

In fact, in Britton’s study, 60% of the participants reporting distressing experiences were meditation teachers, rebutting Davidson’s argument that experienced meditators don’t end up in difficult territory.

While blaming meditators for their negative experience is an unfortunately common tactic from the mindfulness intelligentsia, another strategy is to pretend that adverse effects don’t occur.

Spirit Rock Meditation Center, widely viewed as the mecca of American Buddhism, hosts scores of silent meditation retreats each year. On its website, there are reminders not to bring scented soap due to allergies, articles touting the benefits of meditation, and even a recipe for the gluten-free almond cupcakes served in the center’s acclaimed kitchen. Yet there’s not a single word about a fact every prospective meditator deserves to know: meditation can harm you3.

Vipassana International, the meditation organization that Britton says triggers the most adverse effects, flat-out denies meditation ever goes bad. With 13 retreat centers in the United States and 207 across the globe, Vipassana International likely serves more meditators than any other organization in the world. On its website, it specifically answers the question of whether or not Vipassana meditation can “make you mentally unbalanced.”

The answer given: “No, Vipassana teaches you to be aware and equanimous, that is, balanced, despite all the ups and downs of life.4”

That answer likely feels cruel to the family of Megan Vogt. Vogt, a 25-year-old Pennsylvania woman with no history of mental illness besides anxiety, committed suicide in 2017 in the aftermath of a 10-day Vipassana retreat. According to media reports, she left the retreat in a psychosis, barely recognizable to her family. On the way home from the retreat center, she tried to commit suicide by jumping out of her car and eventually spent time in a psychiatric ward.

Ten weeks later, she jumped off a bridge to her death.

Before her death, Vogt sent two emails to the retreat center about her challenges, at one point writing that she thought her distress was “a sign that I need to give up my life for a more pure one.”

The responses she received weren’t more than a line or two, saying her message had been forwarded to a teacher, who never reached out.5

What happened to me last year in that chilly cabin in North Carolina? That’s a question I’ve been wrestling with since I left the retreat. As my knowledge of meditation-related distress has increased, it has not made things simpler to understand. In sifting through a patchwork of spiritual, psychological and biological frameworks, I have had to mix and match and to trust less in the words of experts and more in my intuition. It’s been, like much in life, an inside job.

One thing is clear: I have significantly healed over the last 15 months due to a combination of medication, therapy and support groups. However, vestiges of my symptoms do still remain.

The framework that aided most in my recovery is the work of Willoughby Britton, without whom I would be in unimaginably dire straits.6 Britton has had to mop up after the meditation industrial complex and help the people deemed by the Richard Davidson’s of the world as failed meditators or by other spiritual teachers as being congenitally unwell.

She has created an impressive body of work that shows how certain mechanisms of meditation can trigger a traumatic stress response. This approach rejects spiritual interpretations of these experiences for those grounded in neuroscience and physiology. Most heartening is that it’s not simply theoretical, but involves practical steps to heal.

The most powerful, for me, has been a trauma therapy called Somatic Experiencing, founded by the psychologist Peter Levine. Levine argues that humans often inhibit their biological defensive responses, such as fight, flight and freeze, trapping them in the body. Using this model, it’s possible that my meditation practice unleashed a stockpile of latent defensive responses, which emerged so rapidly that my body could not integrate them. One psychological element of my experiences was that I did glimpse some hidden pockets of self-loathing, which could have been a trigger for this response.

I cannot rule out that possibility that, at the same time, I had some sort of “spiritual emergency,” a term coined by the therapist Stanislav Groff and used to describe non-ordinary states of consciousness that are often mistaken for mental illness. Groff’s work and that of his colleagues was helpful in normalizing my experience, but it didn’t provide a coherent framework for healing.

Lastly, it’s easy to make the work of Daniel Ingram and similar meditation teachers a scapegoat for this type of suffering, as his suggestion to meditate through the Dark Night had a catastrophic effect on me and is often cited by distressed meditators as a contributing factor to adverse effects. In fact, stopping meditation was crucial to my recovery. That being said, Ingram has provided a valuable service in describing in-depth the often bizarre and dangerous territory of intensive meditation, which has been whitewashed from our contemporary mindfulness culture.

Perhaps the biggest lesson of this experience was the danger in all-encompassing frameworks, those in which a group of powerful people make truth claims about the “nature of reality” or something similar based upon their own experiences. There are few places where this is more actively happening than the convergence between Western science and Eastern religion, where neuroscientists, psychologists and monks have converged to create a new religion that the scholar David McMahan calls “Buddhist Modernism.7”

These days I rarely meditate, but the quality of mindfulness is a constant in my life. I use it when I need it, but I can turn it off and on. It’s a tool that I can access but doesn’t control me.

A few months ago, I began dabbling with teaching mindfulness again, which may seem surprising. However, I believe that these practices, with the correct framework, dosage, and education, can be a valuable tool for improving mental health. I have seen it repeatedly in my classes. And, perhaps, more important, I feel that I could do something for my students that wasn’t ever done for me: tell the truth.

In one of her papers, perhaps the one most valuable for me, Britton theorized that the effects of mindfulness might follow an inverted U-shaped curve, where at some point therapeutic returns not only diminish but mindfulness could have negative side effects.8

That fits my story like a glove.

I began meditating in search for a decrease in stress and anxiety. I got that, and then somehow became swept away in a new-age super religion without even knowing it. There are parts of this essay that embarrass me. But, when you’re vulnerable and looking for answers, you take what is available. For me, that was the enlightenment pill, and I almost choked on it.

Many who have these types of experiences don’t talk about them publicly. It’s not because they’re not powerful, smart, and strong. It’s because they’re scared that their stories will be greeted with defensiveness, snark and possibly even attacks. I’ve been tempted to do the same.

But lately, I have begun counseling other meditators in distress, and I see the fear in their eyes. It reminds me that I have some work to do before I let this wound close. It’s this essay, the act of speaking out, of rendering my story in a public way, that I need to complete to put this chapter of life behind me. I can’t bear the idea of pushing these experiences under the rug or simplifying them like so many other meditation teachers have done.

If you’re a meditation teacher or hold a powerful position in the mindfulness industry, perhaps take a moment to question what sort of legacy you want to leave. Transparency, honesty and humility are often the core values of religion, but are typically abandoned the moment a sacred idea is critiqued.

Is it the fate of the Western mindfulness movement to follow this trend? Is there some wiggle room around the idea that more awareness is always better? Is there potential for a pause in our desperate attempt to prove that we’ve found a magic bullet for all our ills?

Can we be honest about the negative effects of this practice so people know what they’re getting? Isn’t that an ethical responsibility of being a meditation teacher, no different than how a doctor advises patients of possible side effects?

For me, meditation will always stay close to my heart. There’s something so curious and bizarre about being human that I find it irresistible to occasionally poke around the edges. I’ve shed a lot of baggage over the last 15 months. At the core was the loss of my faith: a faith that had protected me, supported me, answered questions that felt unanswerable, empowered me in the innumerable ways that only faith can.

My faith did not crumble gradually — but collapsed like a Jenga game, leaving me to pick through the ruins and to wonder, with tremulous apprehension, if anything was salvageable. What I found was not the remnants of my Buddhism, but instead slivers of a past self buried under the weight of dogma long ago. There, entombed in the cobwebs of time, was a skeptic, a rebel, an explorer and a writer: a fierce collective primarily interested not in making the world easier or simpler, but in celebrating its insane vastness and complexity. It was something once surrendered as an offering. It is part of myself that I have now reclaimed.

If you think this essay may be valuable to others, please share. If you are interested in reading more of my writing, please subscribe.

Varieties of Contemplative Experience Study, PLOS

Meditation Is a Powerful Tool and For Some it Goes Terribly Awry, Vice

Gluten-Free Almond Cupcakes, Spirit Rock Meditation Center

Questions and Answers About the Technique of Vipassana

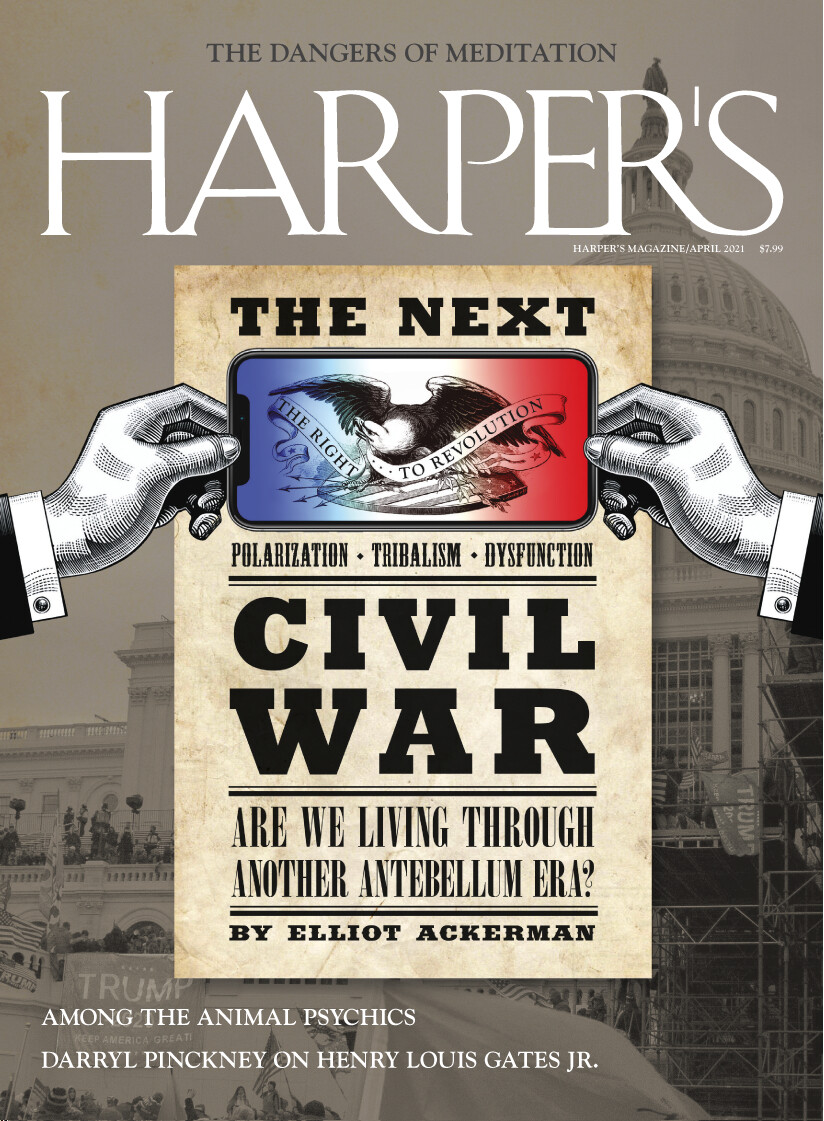

Lost in Thought, Harpers Magazine

Cheetah House, Resources for Meditators in Distress

The Making of Buddhist Modernism, David McMahan

Can Mindfulness Be too Much of a Good Thing? The Value of A Middle Way, Science Direct

[34](javascript:void(0)) 56 [Share](javascript:void(0))

Jul 17, 2021Liked by Dan Lawton

Thanks so much for this, Dan. The dangers of meditation – especially for people who have experienced trauma, anxiety intensities, and recurrent episodes of panic (notice that I’m not calling any of these things disorders) – has been well documented, but silenced, ignored, or shouted down.

And the ethical lapses involved in selling mindfulness to captive audiences in the workplace, schools, prisons, and other high-control organizations are also not being addressed with enough seriousness.

If something is powerful, it can be powerfully healing and also powerfully harmful.

I grew up in the meditation and yoga cultures and saw so much trouble there that, as a teen, I developed my own practices that don’t lead to dissociation, depersonalization, or emotional disruptions. I thought I was being impertinent, but i really couldn’t tolerate meditation or the culture of certainty around it.

I see now that I had a pretty good idea! Thanks for telling your story. I’m certain that people will tell you that you weren’t doing meditation right, but that’s a part of the silencing culture. These negative effects are real and not disclosed, which leads to unnecessary suffering. I don’t think Buddha would like that!

[12](javascript:void(0))[Reply](javascript:void(0))

Jul 19, 2021Liked by Dan Lawton

Thanks for sharing, Dan. Beautifully written essay, and glad to hear you are finding integration and healing.

I once was a Goenka Vipassana meditator too, went on 3 of the 10-day courses. I think part of the problem with that tradition specifically is the long hours. It’s the ultramarathon of meditation, and injuries are inevitable. They absolutely know about injuries, that’s why they have a checklist of things they reject people for, like doing QiGong because they know about things like QiGong sickness. Or if you do other meditation practices they reject you because of the risks of combining practices. But of course even if you do just Goenka’s body scan technique perfectly, it can be an intense ride and can break a person. Also the “one technique only” dogma is very harmful for intermediate-to-advanced meditators, because that’s exactly when you need to explore different approaches like Somatic Experiencing or therapy or something else to integrate other stuff, since you’ve reached the point of diminishing returns with Goenka’s body scan method.

I agree we absolutely need to talk about the risks of meditation. I got a CT scan last year and I had to sign a waiver that said there was a 1 in 100,000 chance I would just die from the scan due to a rare side-effect. We don’t yet know how rare or common meditation side-effects are, but we should at least do due diligence and let people know they exist. I know loads of people personally who have had spiritual emergency or other negative side-effects from meditation, Kundalini yoga, yoga asana, or other spiritual practices. In every large retreat you can practically guarantee one or two people there are having a mental health emergency.

We also need a lot more studies to determine causation. I think it’s very likely that meditation, especially very intensive retreat style meditation, has rare but consistent side-effects. But without a control group, how can we know for sure?

Part of the problem is we don’t talk about psychosis or mental health emergencies generally, let alone in meditation communities with religious bias towards their technique being always good. When we think of “crazy” we tend to have an image in our mind of someone experiencing psychosis, a relatively common human experience that most people recover from if they are given the proper support. Instead we treat people going through mental health crisis as lepers and shunt them off to the margins of society.

I do think probably iatrogenic spiritual injury can happen to anyone at any time, but I also suspect different approaches to meditation could reduce risk. Super intense retreat schedules I think are likely to increase risk, just as super intense running schedules are likely to increase the risk of shin splints or knee injury. People who are injured by meditation often, like you, seek out techniques designed to work with trauma. But why wait? We should start from the beginning with trauma-aware and trauma-transforming methods. Life itself is traumatic for most of us, even if we don’t qualify for an official PTSD diagnosis. We need approaches to mindfulness that actually inhibit the sympathetic nervous system response from Day 1, not simply increase sensory clarity more and more until it is overwhelming.

Realistically you cant really do anything without some risk of adverse effects. Even with something like exercise you will probably find people who had adverse results.

I’d also be interesting to see if some of these resulted in people simply not meditating properly, especially with the rise of quick and easy mindfulness certifications I’d imagine there probably are some less than qualified instructors out there.

Personally I think it is depends on what kind of meditation we are doing.

If it is just Buddhanussati, Devatanussati or casual Metta Bhavana, then I think everyone can do it, without problems.

But if we talking about Kasina meditations, repulsiveness of body meditation or charnel ground meditation, then we need a qualified teacher.

Incidence and Predictors of Meditation-Related Unusual Experiences and Adverse Effects in a Representative Sample of Meditators in the United States

Nicholas T. Van Dam https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1131-0739 nicholas.vandam@unimelb.edu.au, Jessica Targett, […], and Julieta Galante https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4108-5341+2View all authors and affiliations

https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026241298269

Abstract

Estimates suggest that meditation use is comparable to mental-health-service access in the United States. Understanding meditation-related adverse effects (AEs) is therefore critical. We aimed to (a) estimate the incidence of meditation-related unusual experiences and AEs using different methods and (b) identify sociodemographic and health-related characteristics predicting their incidence. We conducted a cross-sectional, population-based survey of 886 U.S. adults (approximately representing population age, gender, and race/ethnicity) stratified by lifetime meditation experience and type. Of the participants, 96.6% reported an unusual experience, 58.4% reported an AE (Inventory of Meditation Experiences), 78.3% endorsed one or more items on the Meditation-Related Adverse Effects Scale, 31.4% endorsed experiencing a challenging/difficult/distressing experience, and 9.1% reported functional impairment because of AEs. In a robust multiple regression, psychological distress, psychoticism, unusual beliefs, and meditation-retreat participation were positively associated with unusual experiences and AEs. It is essential that (a) potential meditators are informed about possible experiences, (b) providers consider risk factors, and (c) AEs are routinely and actively monitored.

I think that there are many factors.

There is one monk who had dormant major mental health issues and he could go into jhana for 6 hours at a time. Meditation and staying immersed for that long was suspected to be the cause for the meltdown. However, his father has bipolar and his brother has bipolar too. It appears to be a genetic condition rather than a meditational caused condition. Perhaps a trigger? Maybe. I think I heard long ago that drugs and alcohol can onset the genetic mental health issues quicker than normal. It is my belief that meditation can affect this onset condition. Or who knows maybe meditation could delay it to a point, and then it came on like a giant surge. It is clear that psychiatric conditions come at later ages. I think this was unavoidable.

So there needs to be research into other factors especially genetic factors that go unreported for meditation “causing mental illness.”

Other issues persist like the association of using psychology with buddhism and mixing the two. Many people try to replace therapy or mix therapy and medical treatment with buddhism. In my Buddhist Psychology class, we discussed that Buddhist Psychology is philosophy, but psychiatry is a medical science. Treating the causes are different.