I don’t know which part within The Atthasālinī you read this in, but I had read the same statement within Sammohavinodanī on the second book of the Abhidhamma, as follows:

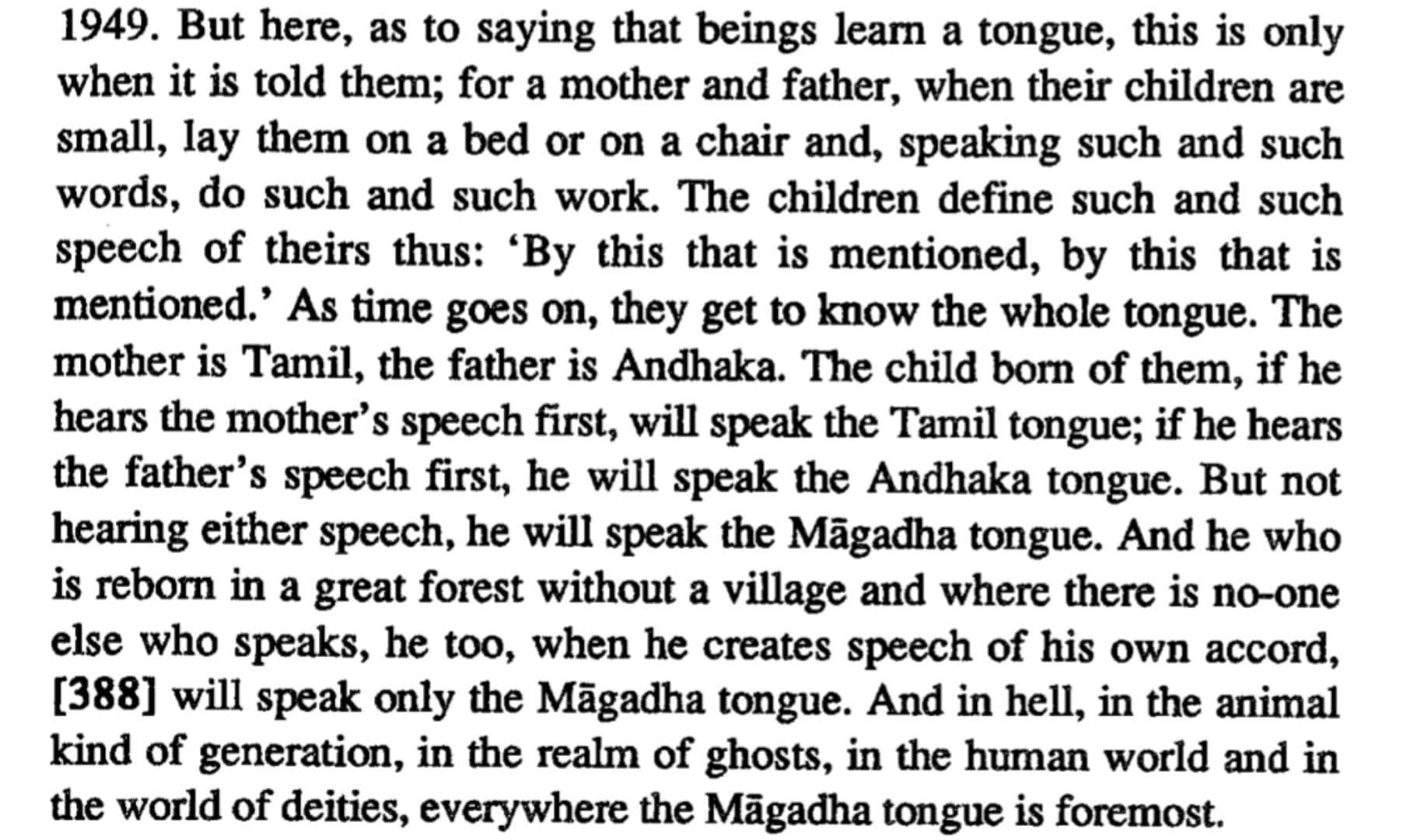

The tradition asserts that the Buddha spoke and taught in Māgadhī, the dialect of the Indian region of Magadha. Furthermore, considering Māgadhabhāsā (our Pāli) as the root language (mūlabhāsā) of all Buddhas and all other beings, it is regarded as the speech of the āriyans (e.g., Sp.i.255). and thereof it if children grow up without being taught any language, they will naturally begin to speak the Magadha language. This language is widespread throughout Niraya, among lower animals, petas, humans, and devas (VibhA.387f).

On the other hand, this part of the commentary pertains to Vibh 15, and this chapter bears the title Paṭisambhidāvibhaṅga (Analytical Knowledge). It affirms the following:

What states are neither-good-nor-bad? At the time when having done, having accumulated bad action, resultant eye consciousness arises, accompanied by indifference, having visible object, :P: ear consciousness arises, accompanied by indifference, having audible object, :P: nose consciousness arises, accompanied by indifference, having odorous object, :P: tongue consciousness arises, accompanied by indifference, having sapid object, :P: body consciousness arises, accompanied by painful feeling, having tangible object; at that time there is contact; there is feeling; there is perception; there is volition; there is consciousness; there is pain; there is one-pointedness of consciousness; there is controlling faculty of mind; there is controlling faculty of pain; there is controlling faculty of vital principle; or whatever other dependently arisen non-material states there are at that time. These states are neither-good-nor-bad. Knowledge of these states is analytic insight of consequence; that philology by which those states are designated; knowledge of the actual philological definition of that (designation) is analytic insight of philology; that knowledge by which he knows those knowledges | thus, “these knowledges clarify this meaning”, knowledge of (these) knowledges is analytic insight of knowledge.

Vibh 15

The Abhidhamma’s explanation of consciousness and mental factors operating at the ultimate level, independent of conventional language designations, provides the foundation for understanding why Māgadhī is the natural language. When consciousness manifests its expressive capacity without external linguistic conditioning, as the Sammohavinodanī demonstrates through the example of a person born in isolation, it naturally does so in Māgadhī. This indicates that Māgadhī most closely corresponds to the actual structure of ultimate reality (paramattha), which explains why it emerges spontaneously when untainted by conventional linguistic influences and why it is the language chosen by all Buddhas to express the Dhamma.

Venerable Bhadantācariya Buddhaghosa remarked that Pāli (By referring to it as Māgadhabhāsā), is “easy to convey the meaning” (atthaṃ āharituṃ sukhaṃ hoti, literally: “it is simple to bring forth the meaning”). He further noted that “as soon as the sound reached the ear, the meaning appeared in countless ways, in myriad forms” (sote pana saṅghaṭṭitamatteyeva nayasatena nayasahassena attho upaṭṭhāti, Vibh-a 718).

This leads us to affirm that Pāli is a “natural language” defined within natural terminology (‘sabhāvanirutti’), as its inherent nature.

the specific point is: What is the obstacle to not accepting this? (Leaving the door open for other matters, here as an example and not limited to it).

The commentaries are infallible; it was recited by the Most Venerable Elder Mahākassapa and the Arahants after him during the First Council. The authority of the commentary is absolute, complete, and supreme. If we denounce their perfection, then we must, in turn, denounce the Mūla itself. For the individuals who recited the commentaries also recite the root text. And what will remain for us to say if we do this?, except that we will fragment the Buddha-Dhamma.